I read parts of the exhaustive Going Clear, but I didn’t finish it. (Trying to do a better job keeping up with quick book reviews these days, and I finally got talked into Goodreads.)

I read parts of the exhaustive Going Clear, but I didn’t finish it. (Trying to do a better job keeping up with quick book reviews these days, and I finally got talked into Goodreads.)

I read Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, and it’s probably my favorite book of the year so far. Like Wilson, I never cared that much for Céline Dion’s music, and hadn’t tried to care, but I came away with a new appreciation for where she came from and some of her shrewd business moves. But it’s not just about the music and industry angle, the good stuff is how he uses Dion as the pivot to talk about taste, and all the baggage that informs our opinions.

Much of this book is about reasonable people carting around cultural assumptions that make them assholes to millions of strangers.

So this is right in my wheelhouse, as taste and opinions are two of my favorite tags here. Some favorite parts…

On pop criticism and critical reevaluation:

If critics were so wrong about disco in the 1970s, why not about Britney Spears now? Why did pop music have to get old before getting a fair shake?

And later, trying to fight your instincts and keep an open mind:

If guilty pleasures are out of date, perhaps the time has come to conceive of a guilty displeasure. This is not like the nagging regret I have about, say, never learning to like opera. My aversion to Dion more closely resembles how put off I feel when someone says they’re pro-life or a Republican: intellectually I’m aware how personal and complicated such affiliations can be, but my gut reactions are more crudely tribal.

On the acknowledged fakeness of shows like American Idol:

For all the show’s concentration on character and achievement, it is not about the kind of self-expression critics tend to praise as real. It celebrates […] “authentic inauthenticity”, the sense of showbiz known and enjoyed as a genuine fake, in a time when audiences are savvy enough to realize image-construction is an inevitability and just want it to be fun. “Authentic inauthenticity” is really just another way of saying “art”, but people caught up in romantic ideals still bristle to admit how much of creativity is being able to manipulate artifice.

On conformity of opinion:

The bias that “conformity” is a pejorative has led, I think, to underestimating the part mimesis – imitation – plays in taste. It’s always other people following crowds, whereas my own taste reflects my specialness.

On middlebrow:

Middle brow is the new lowbrow – mainstream taste the only taste for which you still have you say you’re sorry. And there, taste seems less an aesthetic question than, again, a social one: among the thousands of varieties of aesthetes and geeks and hobbyists, each with their special-ordered cultural diet, the abiding mystery of mainstream culture is, “Who the hell are those people?”

In a section that ties in the work of Pierre Bourdieu, a bit on class and the varieties of capital:

One of Bourdieu’s most striking notions is that there’s also an inherent antagonism between people in fields structured mainly by cultural capital and those in fields where there is primarily economic capital: while high-ranking artists and intellectuals are part of the dominant class in society thanks to their education and influence, they are a dominated segment of that class compared to actual rich people. This helps explain why so many artists, journalists and academics can see themselves as anti-establishment subversives while most of the public sees them as smug elitists.

I love this section on the double-standards about the emotional content of music, especially when it comes to things like sentimentality, tenderness, etc.

Cliché certainly might be an aesthetic flaw, but it’s not what sets sentimentality apart in pop music, or there wouldn’t be a primitive band every two years that’s hailed for bringing rock “back to basics”. Such double-standards arise everywhere for sentimental music: excess, formulaism, two-dimensionality can all be positives for music that is not gentle and conciliatory, but infuriated and rebellious. You could say punk rock is anger’s schmaltz.

In a section talking about all the ways we can love a song, a reminder:

You can only feel all these sorts of love if you’re uncowed by the questions of whether a song will stand the “test of time”, which implies that to pass away, to die, is to fail (and that taste is about making predictions). You can’t feel them if you’re looking for the one record you would take to a desert island, a scenario designed to strip the conviviality from the aesthetic imagination.

And another one:

When we do make judgements, though, the trick would be to remember that they are contingent, hailing from one small point in time and in society. It’s only a rough draft of art history: it always could be otherwise, and usually will be. The thrill is that as a rough draft, it is always up for revision, so we are constantly at risk of our minds being changed – the promise that lured us all to art in the first place.

While I’m wrapping up, I should mention two things those excerpts don’t capture well: 1) the long, smooth, winding essay feel, as it all snaps into place so nicely, and 2) a lot of fascinating detail on Céline Dion herself. She’s a pro.

This book would pair really nicely with two other books I’ve loved: Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, a sort of historical/sociological exploration of class and taste, and The Age of the Infovore, which runs with the idea of open-mindedness and how we’re all so damn lucky to have so much culture at our fingertips.

I read Padgett Powell’s The Interrogative Mood: A Novel?, which is one-of-a-kind. Easy to pick up and chew a few lines at a time, or just surf along the steady waves of questions. Here’s an idea of what you’re in for:

Is there enough time left? Does it matter that I did not specify for what? Was there ever enough time? Does the notion of “enough time” actually make any sense?

Or maybe this:

Have you ever watched bats come out of a wall? How the soft, friendly things keep pouring silently out of the brick? How they have focus, and mission, and you do not?

Not the most representative sample, but I’m not sure there is one. Good stuff. Thanks to Austin Kleon for the glowing recommendation.

I read Tom Bissell’s Magic Hours, a good collection of nonfiction. Just gonna pull out a few parts I really liked. On small towns:

In a small town, success is the simplest arithmetic there is. To achieve it, you leave – then subsequently bore your new big-city friends with accounts of your narrow escape.

Thinking about Stories We Tell last night reminded me of this, on documentaries:

Explanatory impotence is not unique to the documentary but in some ways is abetted by the form. Inimitably vivid yet brutally compressed, documentaries often treasure image over information, proffer complications instead of conclusions, and touch on rather than explore. When a documentary film […] charts the mysteries of human behavior, an inconclusive effect can be electrifying.

Along the same lines, later, on nonfiction…

In the end, great nonfiction writing does not necessarily require any accuracy greater than that of an honest and vividly rendered confusion.

Overall, I enjoyed most of it, but not nearly as much as I liked his more focused, and somewhat more personal book Extra Lives.

It wasn’t a question of keeping away from something, it was a question of something not existing; nothing about him touched me. That was how it had been, but then I had sat down to write, and the tears poured forth.

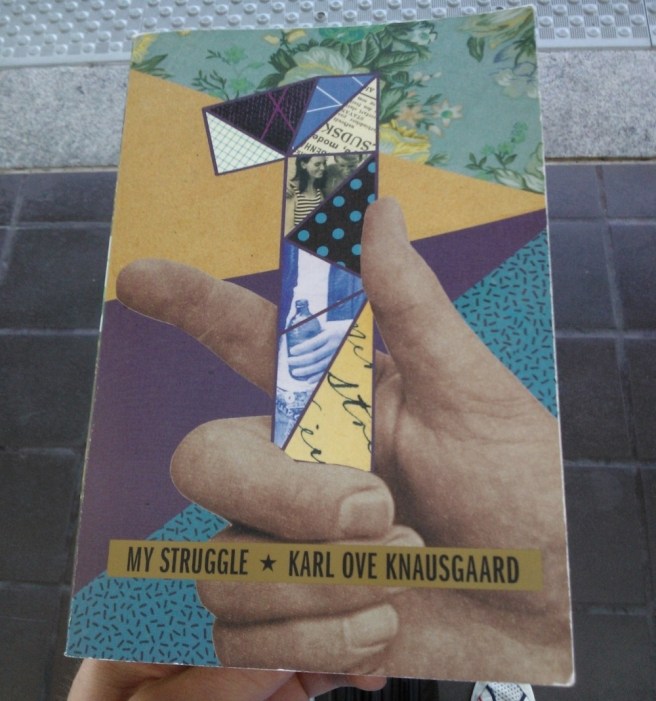

It’s been a while since I finished My Struggle – mid-September, I think – but it has stuck with me. When I finished it, I wasn’t sure if I’d read Knausgård’s second volume, to say nothing of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth. I pre-ordered the second last week.

Reading this book is a strange experience. It’s rarely fun. The book opens with a reflection on death, closes with death, and in between are all manner of musings and journalings about muddling through life and fatherhood. But it’s a great exercise in being aware, a wake-up call. Despite relying on some pretty intense memory-dredging, it doesn’t quite feel sentimental (“Nostalgia is not only shameless, it is also treacherous.”). The challenge seems to be to examine the past so closely that you can let it go – the contrast with what’s actually here and now becomes too stark to ignore.

And there’s a weird addictive quality to it, despite how dark it is sometimes. The writing is mostly functional, rather than poetic or luminous or whatever. And the boldness of his oversharing helps. But it’s the occasional big, beautiful payoff that makes the slogging really worthwhile. (And some of it is indeed pure slog – the 100-page story of a New Year’s Eve beer run is… something else.) There are delights like this description, taken from a section about his college days, when he discovered Theodor Adorno’s writing:

This heavy, intricate, detailed, precise language whose aim was to elevate thought ever higher, and where every period was set like a mountaineer’s cleat.

Such a great image! Or this, trying to capture the feeling of falling in love with a painting:

Yes, yes yes. That’s where it is. That’s where I have to go.

Been there, for sure. I suppose when you write so much without filtering or apparent embarrassment (on life as a teen: “I have never been in any doubt that this is what girls I have tried my luck with have seen in my eyes. Too much desire, too little hope.”), there’s bound to be some memorable parts. Let it all pour out, and see what works. Like this passage early on, when he, a middle-aged guy, is thinking back to what it felt like to be a kid around his father, and using his now-adult perspective to reflect on what it was like to be his father, now that time has made him his father’s peer, in a way:

While my days were jampacked with meaning, when each step opened a new opportunity, and when every opportunity filled me to the brim, in a way which now is actually incomprehensible, the meaning of his days was not concentrated in individual events but spread over such large areas that it was not possible to comprehend them in anything other than abstract terms. “Family” was one such term, “career” another.

Speaking of being a father, here he is on the birth of first child:

There has never been so much future in my life as at that time, never so much joy.

So beautiful. But as Knausgård doesn’t seem to have much of a filter, nothing remains quite that simple or tidy:

Nothing I had previously experienced warned me about the invasion into your life that having children entails. […] Your own worst sides are no longer something you can keep to yourself.

He’s not afraid to acknowledge ambivalence. (That bit, by the way, reminded me of Carolyn Hax talking about introverts having children.) Along with the mundane details – like the dozens of scenes where’s he’s hanging out with someone and making coffee, tea, etc. – there are some more philosophical asides. In a passage that mirrors the opening and the closing of the book, he talks about death and and how our language mirrors the way we don’t quite accept it:

While the person is alive the name refers to the body, to where it resides, to what it does; the name becomes detached from the body when it dies and remains with the living, who, when they use the name always mean the person he was, never the person he is now, a body which lies rotting somewhere. […] Death might be beyond the term and beyond life, but it is not beyond the world.

These little excerpts don’t quite capture it, though. It really is a book better experienced in huge chunks. Recommended.

Filed under: books I’ve reviewed. I also enjoyed this LARB review and this Bookforum interview.

As the Buddha said two and a half thousand years ago, we’re all out of our fucking minds! That’s just the way we are. – Albert Ellis

What a fine book. If, like me, you have ongoing interest in stoicism, happiness, mindfulness meditation, thinking about death and failure, and tend to be a skeptical of your Rhonda Byrne/Tony Robbins types (but are at the same time, kind of amused by them), you’ll probably like Oliver Burkeman’s The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking. In every chapter, there’s some kind of personal connection–an interview, an experiment, field research–but it doesn’t turn preachy or antagonistic. He’s not much for dishy takedowns or “turns out” revelations. He examines a few traditions or lines of thinking, and connects them with an experience. I think he strikes a good balance between his first-person narrative and his research and exploration.

Early on, Burkeman suggests that one weakness in happy thinking is what you might call a reductionist problem: life is messier than that. Most things aren’t binary. Life is full of uncertainty, there are constant threats to our precarious hold on whatever we’ve got going for us, and, to top it all off, there’s a shitty, guaranteed end result:

No matter how much success you may experience in life, your eventual story will be one of failure. Your bodily organs will fail, and you will die.

You have to make peace with that. And blinding, sunny optimism doesn’t always afford the opportunity.

Burkeman finds a practical objection to positive thinking that I hadn’t considered: Kind of like the challenge “do not think of a pink elephant”, when you try to live the admonition to “think positive”, you end up with this constant meta-cognitive scanning. Am I thinking happy? Is this a negative thought? Am I successfully not thinking about bad things X, Y, and Z? You naturally think of negative things while policing yourself for negative thoughts. How can you change this? One alternative is a more stoic approach. Avoid or minimize the labeling in the first place, or confront it honestly and let it go. After all,

Nothing outside your own mind can properly be described as negative or positive at all.

It’s a more global perspective. Outside events run through a filter (our beliefs) and then generate some interior reaction. If you really embrace this, you get more power over how you (choose to) feel.

And how bad can it be, really? That’s another more stoic/realist tactic: face the disaster head-on. Imagine, in detail, how bad it could be. One advantage of this worst-case scenario approach: it “turns infinite fears into finite ones”. I love that.

Another practical barrier to positive thinking I thought was interesting was about affirmations: we simply don’t internalize them very well. And when things like “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough…” just don’t ring true with how we already conceive of ourselves, thinking them is only going to make us more anxious. Even positive visualization can make you relax instead of pumping you up. And I love this line about advice and motivation:

Motivational advice risks making things worse by surreptitiously strengthening your belief that you need to feel motivated before you can act. By encouraging an attachment to a particular emotional state, it actually inserts an additional hurdle between you and your goal.

So, the stoic approach is valuable: it’s gonna suck, you don’t feel like it, and you won’t anytime soon, it might be a disaster, but do it anyway. Whatever “it” is.

In the chapter on Buddhism, non-attachment, and meditation, he brings up Albert Ellis‘ idea of “musturbation”. We become obsessed with things we want. We become absolutist about the results we need. There’s a related idea here: “goalodicy” (coined by Christopher Kayes), where we hang on to and internally defend faulty goals as a way of preserving our identity, because we’ve already invested so much of ourselves in a particular happy outcome. Build things up too much, and you get burned. So meditation is both practice in giving up control, and a way to honestly confront what life brings you. Burkeman quotes a great, great line from Barry Magid:

Meditation is a way to stop running away from things.

A related idea: considering any problems you face, how many of those problems are problems right now? As in, now now. Probably none or few–most problems we have (and our compulsively recycled thoughts about them) are about the past or about the future. Meditation brings you back to this moment, when you can actually do something.

Another way to think about the problem of optimism is that it can turn into a way of chasing security, and fleeing vulnerability. The problem, as Alan Watts says, is that

If I want to be secure, that is, protected from the flux of life, I am wanting to be separate from life.

I loved the final sections about death, too. Burkeman talks about memento mori, and mono no aware, and more broadly the idea of failure and “letting death seep back into life”. Carol Dweck comes up in a short discussion of talent and success, specifically her idea that the mindset we have about success tends to be either “fixed” or “incremental”. That is, we see success in terms of innate talent/ability vs. growth/learning, and thus tend to see failure in terms of dread/threat/identity crisis vs. improvement/opportunity/adaptation. (Let’s make better mistakes tomorrow!) So in the midst of a failure-shy, success-worshipping culture, we get a better sense of community and empathy when we acknowledge mess-ups as an expected, normal, more-than-likely-than-not occurrence. And more practically:

Failure is a relief. At last you can say what you think.

his book would pair well with Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations or Alain de Botton’s Religion for Atheists–I detect similar attitudes in each. For good books on happiness, I recommend Jonathan Haidt’s The Happiness Hypothesis, and Mark Kingwell’s In Pursuit of Happiness.

Often I went to the movies to mess with time, to get it off my back or keep it from staring glumly at me from across the room.

This Is Running for Your Life is a pretty great collection of essays, with a mix that includes some more personal, memoir-ish stuff and some that are a bit more historically-minded, on-the-ground reportage. I don’t think surgical focus is Michelle Orange‘s strong suit here, nor her aim, really. The joy is in the wandering. As she says late in the book,

Perhaps all I can offer is the setting down of a space, one whose highest aim is that you might roam, however elusively, within its borders.

Topics aside, what I really, really appreciated were the regular, like, slap-your-forehead/I-wish-I’d-written-that/I-need-to-read-that-again delights on the level of sentence and word and image, little pivots and reveals from behind the cape. If you’re jazzed by turns of phrase, you’ll find a lot to love here. A fun example:

Ryder’s shivering sad girl underwent a kind of ritual sacrifice in 1999, when newcomer Angelina Jolie devoured her in every frame of Girl, Interrupted and licked the screen. But Jolie was quickly isolated and quarantined as an anomaly; she eventually shed the force of her personality and slipped behind the imperial mask of her beauty.

That’s great stuff. That bit comes from what I think is my favorite essay in the book, “The Dream (Girl) Is Over”, which is about movie stars and bodies and mythologizing and evolving silver screen ideals. (Film is a recurring topic in the book. I can relate.)

Movie is the shorthand that preceded talkie. But it’s the latter term that faded away. It’s the movement that sets the form apart (Action!), and the beauty of bright, moving bodies that transfixes.

The essay, among other things, touches on the ideals we’ve offered ourselves on the screen, from the impossibly dreamy Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, to later muscular heroines like Sigourney Weaver, Linda Hamilton, Madonna. And, yes, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. (Oh, also there’s this great aside on how actresses disrobing becomes an important part of the meta-story, “explicit love scenes invariably described as ‘raw,’ ‘real,’ and ‘brave.'”–cf. Girls?).

Another smart observation on how we talk about bodies:

Men queue up to log specious, self-congratulatory elegies, ascribing vague laments for an earlier era’s voluptuousness to the bodies of the women who inhabited it. Women, meanwhile, get lost in arguments about the scourge of vanity sizing. But the body’s centrality is what sets it beside the point: Marilyn Monroe’s measurements were handed out by the same press agents hawking Theda Bara’s false passports; I knew Elizabeth Taylor’s eighteen-inch waist size before it matched my age. Because they look to our hourglass-starved eyes like more generous, “normal” shapes doesn’t make it so, nor does it retro-exempt former standards from their status as standards.

Some other favorite lines? In one essay that talks about brain scans and movie market-testing:

It’s no wonder we have started pair-bonding with our iPhones. In device attachment resides the old struggle between the possessor and the possessed, the shifting sands of desire and consent. What we respond to is not the gadget itself but its promise of some personal and highly specific gratification.

And a related earlier quote, one hazard of our awesome gadgets and the not-quite-hereness they can engender:

Modern cultural memory is afflicted by a kind of dementia, its fragments ever floating around us.

And a related problem:

What we call nostalgia today is too much remembering of too little.

On email’s subtle, sneaky draw:

Email opened up a kind of perpetually empty stage, an endless call for encores.

A bit from an essay on compulsive running and loneliness:

As a way of escape, distance running is the sensory negative of sexual oblivion.

From a chapter on photography:

Especially when they are held out blindly in big crowds, the screens that have replaced the traditional viewfinder appear to function as a kind of second subjectivity, a third eye to cope with a world that is less often collected with any kind of discretion than amassed in daily reality dumps. So that to raise a camera is mostly to remind yourself: Right now I’m here; I’m here right now.

Reminds me of Field Notes: “I’m not writing it down to remember it later, I’m writing it down to remember it now.” A related aside:

I always laughed when a Dutch friend of mine referred to “making” a photo—a translation glitch he couldn’t keep straight. I just thought it sounded funny, but there is something strange about the one art form we talk about in terms of taking, not making.

In her essay reporting on the development of the DSM-5, which also touches on war and addiction, and growing up:

We reach maturity any number of times—biologically, religiously, legally, academically, socially—before the age of twenty-one, but the imputation rarely sticks. The world will not be informed of your various arrivals, the world informs you. […] Slowly, sometimes moment by moment, small choices about whom and how to be beget bigger ones–shading in the background, scaling out the continuum; striking out villains, fleshing in the overlooked–until the story begins to tell itself, with a fully-fledged hero at its center.

Another good line from that essay, one of my favorite observations in the book:

Treating apparently “new” emotional and behavioral disturbances like biological events would seem to be another evasion of a problem the 12-step program makes plain. It feels significant that the first thing someone seeking that program’s help does is walk into a room filled with other people.

So good. There’s much more range here than what my quotes might indicate. You’re likely to find something that works for you, too. Worth a read.

Alain de Botton’s Religion for Atheists has a simple, reasonable, open-minded premise: whether or not you believe in God/Jesus/Heaven/afterlife/salvation/etc., religions can still be interesting, useful, and consoling. The idea here is to explore function rather than truth. Religious institutions are some of the most successful, influential, widespread, long-lived things that humans have ever done, so there’s a lot to learn.

There’s the idea of community, for one. “Religions know a great deal about loneliness” de Botton writes. And if you’ve been to mass with any frequency, you know how often things like poverty, sadness, failure, and loss come up—because the church “sees the ill, frail of mind, desperate, and elderly as aspects of humanity and ourselves that we’re tempted to deny.” But acknowledging these things can bring us closer, or at least make us more humble.

De Botton talks about this sort of groundedness again later. There’s an earthly pessimism that comes with some religious belief. Hopes are ascribed to the next life, not this one. For this one you just try to do right, be generous, and get by as best you can. This pessimism deflates our hopes a bit, but helps to balance those needy, absorptive, consuming, ever-optimistic desires that come in everyday life. Christianity is sober, where perhaps the secular world is too optimistic, or maybe too cowardly, to face life’s hard facts. I like this line where de Botton summarizes all secular arguments:

Why can’t you be more perfect?

Luckily, “sermons by their very nature assume that their audiences are in important ways lost.” We need teaching, and religion’s insistence on that is pretty useful.

Christianity concerns itself with the inner confused side of us, declaring that none of us are born knowing how to live; we are fragile, capricious, unempathetic, and beset by fantasies of omnipotence.

The ever-seeking nature of secularism can also lead to lack of gratitude. Religions bring us back to the basics. A prayer of gratitude before you eat. Marking the passing of the hours with prayer or the seasons or harvests with celebrations. We need reminders of the transcendent, of our smallness. We need rituals and practices that put us in our place.

Art could do this, perhaps—“We need art because we are so forgetful”. De Botton has a great section on the opportunities that modern museum culture misses out on.

We tend to enter galleries with grave, though by necessity discreet doubts about what we are meant to do in them. […] It would take a brave soul to raise a hand.

Museums have a hard time explaining why they’re valuable. Education, sure. They’re not made for prayer or worship, really. We end up with buildings about history of art-ness. But what about something more ambitious? There’s an opportunity to meet our own psychological, emotional needs. We see placards on the walls about style and era and medium and influence. But just like churches aren’t made to teach us about the history of theology, necessarily, museums need not teach us about art history (exclusively). Why don’t we see an exhibition about Death? Or Parenting? Loss? Courage?

De Botton makes similar arguments about secular education, which is fairly impractical. Things like accounting and psychology are useful, yes, but where are the classes about tensions in marriage, or dying gracefully, or the struggles of friendship? (Of course, a philosopher would argue for these things, of course.)

Topics aside, there’s also the structure and etiquette of the modern class to consider. Lector, desks, students, whiteboard. Boring. Contrast with a vibrant church where the attendees are shouting “Amen” and “Preach on!” and “Thank you, Jesus.” You can’t underestimate the value of rapture and assent and an active audience. Teaching is a kind of performance, too.

What purpose can possibly be served by the academy’s primness? How much more expansive the scope of meaning in Montaigne’s essays would seem if a 100-strong and transported chorus were to voice its approval after ever sentence.

There’s also the idea that religious education isn’t, well… it’s not all that new. But the lack of novelty is a blessing in its own way. It makes room for reflection. The church hasn’t had big discoveries or breakthroughs. But it does a fantastic job for structure, schedules, repetition, and reinforcement of its long-held ideas.

A Catholic lectionary, for example, outlines everything you’ll be reading over the course of three years, with readings matched to season and occasion in the church calendar. If you’re devout and interested, there’s a plan there for you to follow. Even if you’re a casual but regular churchgoer, you’re going to cover a lot of material, and it’ll be appropriate to the season. But what’s the best way and context for me to revisit Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations? Is there a good calendar for reflecting on Leaves of Grass, if that’s your thing? How can you carve out a space for secular reflection in your life? It’s not just a scheduling thing. It’s knowing what to do when the time comes. Church attendance is a kind of rehearsal for life outside its doors, and inside its doors you know exactly what’s going to happen.

Another favorite passage:

An absence of religious belief in no way invalidates a continuing need for “patron saints” of qualities like Courage, Friendship, Fidelity, Patience, Confidence, or Skepticism. We can still profit from moments when we give space to voices of the more balanced, brave, generous–and through whom we may reconnect with our most dignified and serious possibilities.

Again, whether or not Mary gave virgin birth, or whether or not Jesus was also God, or whether or not Saint So-and-so really bled from her hands and levitated? Make your own call. The truth is secondary to De Botton’s argument. The function of these beliefs is to get you to be a better person.

This is one of the best books I’ve read in 2012 so far. Very highly recommended.

One overriding sense that I get from Tyler Cowen’s books (and the blog he co-writes) is that he could explain a lot more in more exhaustive depth and detail, but prefers not to do so. The brainpower is there, for sure, and the writing is clear, but the feeling is that he wants me to think rather than be spoonfed. I appreciate this.

You might have heard of The Age of the Infovore under its earlier name, Create Your Own Economy, which maybe explains the contents a bit better (his own summary). Here’s the idea: we live in a crazy modern world etc. etc. information overload etc. etc. BUT the optimistic take is that this cultural explosion coupled with technological advancement means it’s easier and easier for us to assemble these cultural pieces in ways that are meaningful for each of us as individuals.

One result of the internet, I think, is that it makes almost everyone smart more eclectic, whether in terms of substance or presentation.

Which ties in with a later argument…

The mixing of populations lowers the cost of being unusual.

And similarly…

As cultural production becomes more diverse, more and more art forms will be directed at pleasing people with unusual neurologies. More and more of the aesthetic beauty of the world will be hidden to most observers, or at least those who don’t invest in learning.

And luckily, that applies not just to the consumers of art but the art itself. The neurology thing comes up again and again, because one of the continuing threads throughout the book is autism/Asperger’s. He tries, successfully I think, to show the advantages that these conditions can have. Above-average strengths often appear in the autistic cognitive profile (in sorting/ordering, perception of detail, specialization, pattern detection, accurate recall, etc.) and you could say we’ve begun to use things like the internet to order our lives and pursue our interests in ways that more closely mimic autistic traits. Unfortunately, our culture seems to sweep autistics aside because it’s more stereotypically associated with more observable, less desirable personality/behavioral traits. Much of the book tries to set this straight, and in a typically Cowen-esque approach, see the other side.

So back to maybe the greatest joy of modern life: the way we can delve into so many different interests (social, intellectual, cultural, spiritual, etc.) and media (books, blogs, movies, music, etc.) at the same time. And at this point I realize I’m writing this while listening to Mbalax music and texting with a couple friends. While the immediate outside impression-at-a-glance is of overwhelm or disorder, this stuff usually relates to our long-term interests:

While it is easy to observe apparent overload in our busy lives, the underlying reality is subtler. The common word is “multitasking” but I would sooner point to the coherence in your mind than regard it as a jumbled or chaotic blend. The coherence lies in the fact that you are getting a steady stream of information to feed your long-run attention. No matter how disparate the topics may appear to an outside viewer, most parts of the stream relate to your passions, your interests, your affiliations, and how it all hangs together. […] The emotional power of our personal blends is potent, and they make work, and learning, a lot more fun. Multitasking is, in part, a strategy to keep ourselves interested. […] The self-assembly of small cultural bits is sometimes addictive in the sense that the more of it you do, the more of it you want to do. But that kind of addiction doesn’t have to be bad. Anything good in your life is probably going to have an addictive quality to it, as many people find with classical music or an appreciation of the Western classics, or for that matter a happy marriage. Shouldn’t some of the best things in life get better the more you do them?

Cowen has a definite anti-snob bent. Not a cultural relativist per se, but a similar word to the title, “omnivore”, definitely fits. One chapter analogizes modern culture and marriage:

Many critics of contemporary life want our culture to remain like a long-distance relationship, with thrilling peaks, when most of us are growing into something more mature. We are treating culture like a self-assembly of small bits, and we are creating and committing ourselves to a fascinating daily brocade, much as we can make a marriage into a rich and satisfying life. We are better off for this change and it is part of a broader trend of how the production of value—including beauty, suspense, and education—is becoming increasingly interior to our minds.

I love that idea of a “daily brocade”. Speaking of texting and such, here’s a bit on phone calls:

When you make a cellphone call, you open yourself up to being asked questions. You have to commit yourself on matters of tone and also on key information, such as telling your mother where you are and what you are doing and why you didn’t call earlier. A phone call is actually a pretty complicated emotional event and that is one reason why so many people remained “cellphone holdouts” for so long. […] A phone call is a demand on you. A phone call is a chance to be rejected. And a phone call is a chance to flub your lines or overplay your hand.

On the internet’s potential to open your mind politically-speaking:

Being a Democrat, Republican, Libertarian, etc. doesn’t many any single thing for what we are actually like as human beings. One thing we do on the web is seek out others who are like us in non-political ways and then we cement those alliances and friendships. Over time, we will discover that many of these truly similar people do not in fact share our political views. Then we realize that politics isn’t as important as we used to think.

Here’s a nice/terrifying bit on education that I first read on Ben Casnocha’s blog. Comparing high-school-only grads to college grads is common, but if you really want to control, you have to compare college grads to people who think they’re being college-educated to find out if it’s actually working…

It’s now well-known in the medical literature that a medicine needs to be compared to a placebo, rather than to simply doing nothing. Placebo effects can be very powerful and many supposedly effective medicines do not in fact outperform the placebo. The sorry truth is that no one has compared modern education to a placebo. What if we just gave people lots of face-to-face contact and told them they were being educated? I’m not sure I want to know the answer to that question. Maybe that’s what current methods of education already consist of.

I really liked his chapter on “The New Economy of Stories”. You’ll get a good idea of what he has to say if you watch his awesome TEDxMidAtlantic talk on stories.

Some of this branches off from economist Thomas C. Schelling’s essay, The Mind As a Consuming Organ.

Schelling emphasizes that we “consume” stories through memories, anticipations, fantasies, and daydreams. Concrete goods and services, such as Lassie programs, help impose order and discipline on our fantasies and give us stronger and more coherent mental lives. Of course consuming stories is not just about watching television, even though the average American does that for several hours in a typical day. If the tube bores us, we play computer games, read novels, reimagine central events in our lives, spin fantasies, or listen to the narratives of friends.

One way we tell ourselves stories is in how we use our money. (A book that’s become a sort of touchstone for me, Geoffrey Miller’s Spent, comes at these ideas from a similar angle):

You’re not just buying a sneaker, you’re buying an image of athleticism and an associated story about yourself. It’s not just an indie pop song, it is your sense of identity as the listener and owner of the music. If you give to Oxfam, yes you want to help people, but you also are constructing a narrative about your place in the broader world and the responsibilities you have chosen to assume. The Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa wrote: “The buyers of useless things are wiser than is commonly supposed—the buy little dreams.” That is a big part of what markets are about. Whether you are buying cosmetics, a lottery ticket, or an oil painting, you are constructing, defining, and memorializing your dreams into vivid and physically real forms.

And it’s important to keep in mind that these dreams, the stories we tell ourselves, may not be so special or unique to us:

Hollywood blockbusters… end up drained of vitality and risk-taking in an effort to appeal to the least common denominator in a large group of people. We’re less likely to see that the same logic applies not just to the Hollywood studios but also to ourselves. In this way I am pretty typical. Some of the inputs behind my deepest personal narratives suffer from the least-common-denominator effect. The logic applies to my dream. To my fantasies. To my deepest visions of what I can be. I treasure those thoughts and feelings so much but in reality I pull a lot of them from a social context and I pull them from points that are socially salient. That means I pull them from celebrities, from ads, from popular culture, and most generally from ideas that are easy to communicate and disseminate to large numbers of people. We all dream in pop culture language to some degree.

This next quote is all Pessoa, writing perhaps too stridently about the dangers of novelty, but it’s worth considering:

Wise is the man who monotonizes his existence, for then each minor incident seems a marvel. A hunter of lions feels no adventure after the third lion. Fro my monotonous cook, a fist-fight on the street always has something of a modest apocalypse… The man who has journeyed all over the world can’t find any novelty in five thousand miles, for he finds only new things—yet another novelty, the old routine of the forever new—while his abstract concept of novelty got lost at sea after the second new thing he saw.

A later chapter goes into art and culture and aesthetics. Branching off some ideas from neurology and from David Hume’s “Of the Standard of Taste”:

Sociological approaches to cultural taste often imply that taste differences are contrived, artificial, or reflect wasteful status-seeking. The result is that we appreciate taste differences less than we might and we become less curious. Neurological approaches imply that different individuals perceive different cultural mysteries and beauties. You can’t always cross the gap to understand the other person’s point of view, but at the very least you know something is there worth pursuing.

I liked the argument here about musical complexity, but surely the argument applies anywhere else you have cultural competence:

An issue arises if you get “too good” at finding the order in music. You must resort of bigger and bigger doses of informational complexity to achieve the prior effects that were so enjoyable. It’s a bit like needing successively stronger doses of heroin, wanting to move beyond Vivaldi, or more prosaically having to switch from one pop song to the next. Don’t we all do that? But the metric for the right amount of complexity differs across listeners, even across listeners with the same degree of musical experience and education.

And this ties in with how we evaluate cultural works…

The most common reaction is simply to evaluate the aesthetic perspective through the taste of either the public or the educated critics. We privilege those perspectives either because they have social status or because, in the case of the consumers, they have buying power and thus they command the attention of the media. So if it is serial killer stories, maybe the critics call it too lowbrow and talk about the decline of our society. If it is atonal music, it gets labeled as too inaccessible or too highbrow or it is claimed that the academic composers are perverse and self-indulgent. Most cultural criticism is staggering in how much it begs the question of what is the appropriate middle ground.

Boom. Read this book.

I don’t have much to say about On Being Ill other than it’s incredibly short and its meanderings in that space cover the spectrum from silly to sentimental. You will spend perhaps 30 minutes reading this book. I heard of it via Tyler Cowen’s breathless recommendation.

It’s hard to block quote such a short flowing text, but I like these next couple passages. Here’s one at the heart of the book: people don’t write about pain much. It’s overlooked by the great writers, and thus we have no words to steal or clichés to rely on:

The merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry. There is nothing ready made for him. He is forced to coin words himself, and, taking his pain in one hand, and a lump of pure sound in the other (as perhaps the people of Babel did in the beginning), so to crush them together that a brand new word in the end drops out.

And I think most can relate to the the perverse sort of joy we take in being sick, reclining, casting off social graces, embracing our misery:

There is, let us confess it (and illness is the great confessional), a childish outspokenness in illness; things are said, truths blurted out, which the cautious respectability of health conceals. About sympathy for example—we can do without it. That illusion of a world so shaped that it echoes every groan, of human beings so tied together by common needs and fears that a twitch at one wrist jerks another, where however strange your experience other people have had it too, where however far you travel in your own mind someone has been there before you—is all an illusion. We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others. Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest in each; a snowfield where even the print of birds’ feet is unknown. Here we go alone, and like it better so. Always to have sympathy, always to be accompanied, always to be understood would be intolerable. But in health the genial pretense must be kept up and the effort renewed—to communicate, to civilise, to share, to cultivate the desert, educate the native, to work together by day and by night to sport. In illness this make-believe ceases.

Imagine Marilyn Monroe, the star commonly thought to be an airhead, keeping up with Somerset Maugham’s birthday and taking the trouble to send him a telegram.

Spiritual experiences are easy to put into words, as long as you stick to cheesy, clichéd ones.

It’s a great book, let’s get that out of the way before we proceed. Just know that Bill Simmons is a carefree, garrulous writer and it is obsessively focused on basketball. It might not be your thing. One of the best practices when I was reading this one was to keep the iPad nearby so I could do a little backgrounder on legendary players I’d never heard of, and, more importantly, keeping YouTube handy to look up amazing dunks, passes, etc. If you haven’t followed basketball, there is a learning curve. On the upside, like I told Justin, reading this book after the recent playoffs, finals, The Decision, etc. has me more interested in basketball than I’ve ever been.

The biggest parts of the book cover Larry Bird, Russell vs. Wilt, The Secret (e.g. TEAMWORK), ranking the best players ever, and ranking the best teams ever. All in obsessive detail. You can open a page anywhere in the book, and in short order stumble on a really good argument about something. In a 3-page section on Elvin Hayes, Simmons lists 5 reasons that Hayes stands out. In item #5, there’s a little mini-essay on the fall-away/turnaround shot:

My theory on the fall-away: it’s a passive-aggressive shot that says more about a player than you think. For instance, Jordan, McHale and Hakeem all had tremendous fall-aways—in fact, MJ developed the shot to save his body from undue punishment driving to the basket—but it was one piece of their offensive arsenal, a weapon used to complement the other weapons already in place. Well, five basketball stars in the past sixty years have been famous for either failing miserably in the clutch or lacking the ability to rise to the occasion: Wilt, Hayes, Malone, Ewing and Garnett. All five were famous for their fall-away/turnaround jumpers and took heat because their fall-aways pulled them out of rebounding position. If it missed, almost always it was a one-shot possession. On top of that, it never leads to free throws—either the shot falls or the other team gets it. Could you make the case that the fall-away, fundamentally, is a loser’s shot? For a big man, it’s the dumbest shot you can take—only one good thing can happen and that’s it—as well as a symbol of a larger problem, namely, that a team’s best big man would rather move away from the basket than toward it. […] So here’s my take: the fall-away says, “I’d rather stay out here.” It says, “I’m afraid to fail.” It says, “I want to win this game, but only on my terms.”

Woah, right? Coming up organically in a discussion about a specific player we get a really interesting observation on the game itself, couched in a super-fan/nerd’s historical mastery, with some speculative psychology delivered in the kind of friendly/authoritative tone you’d hear at a bar. A later section on Kobe Bryant looks at his career through the lens of Teen Wolf, vacillating between the team-player (Michael J. Fox) and the devastating ball hog/alpha dog (Wolf). Maybe the better movie analogy is thinking of Tim Duncan like Harrison Ford:

If you keep banging out first-class seasons with none standing out more than any other, who’s going to notice after a while? There’s a precedent: once upon a time, Harrison Ford pumped out monster hits for fifteen solid years before everyone suddenly noticed, “Wait a second—Harrison Ford is unquestionably the biggest movie star of his generation!” From 1977 to 1992, Ford starred in three Star Wars movies, three Indiana Jones movies, Blade Runner, Working Girl, Witness, Presumed Innocent and Patriot Games, but it wasn’t until he carried The Fugitive that everyone realized he was consistently more bankable than Stallone, Reynolds, Eastwood, Cruise, Costner, Schwarzenegger and every other peer. As with Duncan, we knew little about Ford outside of his work. As with Duncan, there wasn’t anything inherently compelling about him. Ford only worried about delivering the goods, and we eventually appreciated him for it. Will the same happen for Duncan one day?

If there is a weakness, it’s that the occasional jokey celeb-bashing comes up really lame and unnecessary. But that’s a small price to pay for 700+ quality pages and a comparable number of entertaining footnotes. Worth a read!

Who had light and who did not? What did different types of people do with their newfound hours? How did street lighting change public behavior? (Once drinkers could move safely between taverns, instead of perching on a single tavern stool all night … the streets became far rowdier; prostitutes previously confined to brothels could now sell their wares al fresco.) With increased mobility and safety, those who could afford lighting stayed up later. Sleeping in became a mark of prestige. Meanwhile, those who lived near the gasworks — never located in a city’s high-rent district — endured foul-smelling and dangerous emissions.

(via)

We were delighted to have jobs. We bitched about them constantly. We walked around our new offices with our two minds.

Then We Came to the End was Joshua Ferris’ first novel. I knew about it before I read it mostly because it was written in the first-person plural. We did this, then we did that, so-and-so told us about that guy. The cast is a group of employees in an advertising agency on the down-and-out. I think this one could have been chopped down a bit, but what’s there is still pretty good. And it reads so quickly, it’s not a big deal. The setting and tone reminded me a lot of Matt Beaumont’s book, “E”. The employees gossip, connive, overreact, speculate. Ferris has a great ear and eye for the office, a great observer of office life:

He came by each one of our individual offices, he visited the cubicles and the receptionists. We even saw him talking to one of the building guys. They hardly said anything to anyone, the building guys. Just stood on their ladders handing things up and down to one another, speaking in hushed tones.

And body language:

You didn’t talk about money or job security during a time of layoffs, not in the tone she had taken, and not when you were friends. The silence extended into awkward territory.

[…]

“I wasn’t trying to be snide just then,” she said, finally sitting down, reaching out to touch the edge of his desk as if it were a surrogate for his hand.

And this bit about cuts and promotions:

The point was we took this shit very seriously. They had taken away our flowers, our summer days, and our bonuses, we were on a wage freeze and a hiring freeze, and people were flying out the door like so many dismantled dummies. We had one thing still going for us: the prospect of a promotion. A new title: true, it came with no money, the power was almost always illusory, the bestowal a cheap shrewd device concocted by management to keep us from mutiny, but when word circulated that one of us had jumped up an acronym, that person was just a little quieter that day, took a longer lunch than usual, came back with shopping bags, spent the afternoon speaking softly into the telephone, and left whenever they wanted that night, while the rest of us sent e-mails flying back and forth on the lofty topics of Injustice and Uncertainty.

They all have the ring of truth. Sandwiched between the sillier bits, there’s a pretty amazing little intermezzo chapter, “The Thing to Do and the Place to Be”. That one focuses on one of the characters, a manager, who’s struggling to face an upcoming surgery. It’s quite touching.

As the book carries on, the loose, manic tone can start to wear a bit thin. But then, the mood does change. Employees are fired or move on. This “we” that you’ve been a part of breaks up. Former co-workers reunite, have a few drinks, and move on. In the end, the most clever part about that narration is that I really related to it, as corny as it might sound. What makes this book worthwhile is not that it pokes fun at office life, but it helps you to value it.

There is plenty of good discussion of the book elsewhere. I also thought this comparison of “Then We Came to the End” with Tim O’Brien’s “The Things We Carried” was really interesting.

The Unlikely Disciple chronicles Kevin Roose’s semester “abroad”–he transfers colleges for a semester, from Brown University to Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University. This is exactly the kind of nonfiction I like: adventurous, curious, open-minded, respectful. You get a sense of his attitude in the Acknowledgements section, where Roose’s final thank-you is to the students, faculty and administration at Liberty: “By experiencing your warmth, your vigorous generosity of spirit, and your deep complexity, I was ultimately convinced—not that you were right, necessarily, but that I had been wrong.” I love that attitude. LOVE.

Why did he do it? Unfamiliarity, mostly:

One recent study showed that 51 percent of Americans don’t know any evangelical Christians, even casually. And until I visited Thomas Road, that was me. My social circle at Brown included atheists, agnostics, lapsed Catholics, Buddhists, Wiccans, and more non-observant Jews than you can shake a shofar at, but exactly zero born-again Christians. The evangelical world, in my mind, was a cloistered, slightly frightening community whose values and customs I wasn’t supposed to understand. So I ignored it.

I’m in the half that knows quite a few evangelicals, so it was really refreshing to see them treated sympathetically. It is so easy to dismiss crowds you might not agree with, or that you only know by association with FOX News (shudder). Roose offers a bunch of anthropological observations, which I found to be the best part, because many of them ring so true:

Outside of Jane Austen novels, nowhere is marriage a more frequent topic of conversation than at Christian college.

He also talks a bit about how, even at an evangelical college, everybody doubts… There’s a sort of paranoia about yourself and a concern for others that animates social life. What he first perceives as prying (“Are you saved?”) is actually an expression of genuine concern. And at the same time, this paranoia is balanced with a kind of self-help/empowerment vibe. Sin and salvation are two sides of the same coin:

Of all the people I expected to have a moral awakening this semester, Joey was at the bottom of the list. Liberty does this to you, though. It tempts you with the constant possibility of personal realignment.

Later in the book he joins a group for a spring break evangelism trip, down at the wild, sinful beaches of Florida. No success. Part of what cripples this crowd is a language barrier:

Claire’s other problem is total linguistic isolation. She, like many other Liberty students, speaks in long, flowery strings of opaque Christian speak. When a twenty-something guy named Rick tells Claire he doesn’t believe in God, Claire sighs and says, “Listen, Rick. There’s a man named Jesus Christ, and he came into my heart and changed me radically. And there is a God who loves you, and who sent his son to die on the cross for you, to take away your sins and my sins, and God shows himself to me every day. When I don’t have hope for tomorrow, Jesus never fails. His love is never ending.”

It’s no surprise that language is one thing that separates particular communities, but I’d never thought about it in a religious context before. Later in the book, when he’s talking about conversion, he echoes the bit about language and community:

Maybe the transition isn’t so smooth when the foreign experiences deal with God. The anthropologist Susan Harding defines a religious conversion as the acquisition of a form of religious language, which happens the same way we acquire any other language–through exposure and repetition. In other words, we don’t necessarily know when we’ve crossed the line into belief.

If there’s a weakness in this book, it’s that I would have liked to read more about the culture that is Liberty University. He says he peppers other people about their history, beliefs, reasons for being at Liberty, etc. (sometimes to the point of raising suspicions of his true purpose there), but it’s mostly about his own experience. This is a fair approach, but there’s still a voyeuristic side of me that would like to dig more into the sociology of the college itself. Anyway, great book. Recommended.

I saw the movie, liked it a lot, heard good things about the book and figured I might as well. I liked this one just fine. I don’t think it’s quite great enough to recommend, but most good fiction has some oh-yes-that’s-just-like-real-life moments and general snippets of good writing worth sharing. Surely everyone knows a couple like this:

Her husband makes it all possible, a software writer flush with some of the fastest money ever generated by our economy. He hangs pleasantly in the background of Kara’s life, demanding nothing, offering everything. They’re a bountiful, gracious people, here to help, who seem to have sealed some deal with the Creator to spread his balm in return for perfect sanity.

A nice bit of airline paranoia:

I turn on my HandStar and dial up Great West’s customer information site, according to which our flight is still on time. How do they keep their lies straight in this business? They must use deception software, some suite of programs that synchronizes their falsehoods system-wide.

After a disagreement with his sister during a road-side stop, she walks away and he philosophizes on male-female argument dynamics:

My sister is dwindling. It’s flat and vast here and it takes time to dwindle, but she’s managing to and soon I’ll have to catch her. There are rules for when women desert your car and walk. The man should allow them to dwindle, as is their right, but not beyond the point where if they turn the car is just a speck to them.

On childish yet important body-language politics during a business lunch:

He chooses a two-setting table on a platform and takes the wall seat. From his perspective, I’ll blend with the lunch crowd behind me, but from mine he’s all there is, a looming individual. Fine, I’ll play jujitsu. I angle my chair so as to show him the slimmest, one-eyed profile. The look in my other eye he’ll have to guess at.

On Denver and arts scenes:

I’ve been told my old city possesses a “thriving arts scene,” whatever that is; personally, I think artists should lie low and stick to their work, not line-dance through the parks.

I felt pretty torn about this one. I’d been following Gretchen Rubin’s blog about the Happiness Project for a while and wondered what extra stuff would be in the book. I got it from the library, so I’m not sure that it matters as the only cost to me was time. Luckily she’s a really fluid writer and it’s a quick read, so it’s not in the “waste of time” category. Good parts:

If there’s a downside, it’s that I wish she’d shared more of the studies she read up on (surely a ton), and less of the personal anecdotes of how she applied them. But then again, I wonder if I’d say the opposite if the reverse were true? Either way, you can probably get the most bang for your buck by ripping through the best-of section over on her site. Tyler Cowen says “On net, Gretchen’s tips will enhance your happiness.” I suspect this is true.

I like David Byrne, but I feel really ambivalent about this book. On the one hand, there are some great gems and little thought-bits that come out of a curious mind. On the other hand, as the title so clearly points out, it’s diaristic. There’s a good amount of day-to-day humdrum “this is what I did here, this is what I did there” stuff to wade through. With that said, here are some parts I especially liked:

On the meta-ness of ringtones:

Ring tones are “signs” for “real” music. This is music not meant to be actually listened to as music, but to remind you of and refer to other, real music… A modern symphony of music that is not music but asks that you remember music.

Although he praises Europe’s cultivated, park-like landscape, in particular the “manicured” blend of man and nature in Berlin, he finds it

a bit sad, I think, that my visual reference for an unmediated forest derives from images in fiction and movies. Sad too that the forest in this preserved area was once quite common, but now lives on mainly in our collective imaginations.

Early in the book he talks about a number of American cities in brief. On the town of Sweetwater, Texas:

I enjoy not being in New York. I am under no illusion that my world is in any better than this world, but still I wonder at how some of the Puritanical restrictions have lingered—the encouragement to go to bed early and the injunction against enjoying a drink with one’s meal. I suspect that drinking, even a glass of wine or two with dinner, is, like drug use, probably considered a sign of moral weakness. The assumption is that there lurks within us a secret desire for pure, sensuous, all-hell-breaking-loose pleasure, which is something to be nipped in the bud, for pragmatic reasons.

And I liked this back-of-the-envelope theory on mating and signaling in Los Angeles:

I don’t know what the male-female balance is in L.A., but I suspect that because people in that town come into close contact with one another relatively infrequently—they are usually physicall isolated at work, at home, or in their cars—they have to make an immediate and profound impression on the opposite sex and on their rivals whenever a chance presents itself. Subtlety will get you nowhere in this context.

This applies particularly in L.A. but also in much of the United States, where chances and opportunities to be seen and noticed by the oppsite sex sometimes occur not just infrequently but also at some distance—across a parking lot, as one walks from car to building, or in a crowded mall. Therefore the signal that I am sexy, powerful, and desirable has to be broadcast at a slightly “louder” volume than in other towns where people actually come into closer contact and don’t need to “shout”. In L.A. one has to be one’s own billboard.

Consequently in L.A. the women, on the face of it, must feel a greater need to get physically augmented, tanned, and have flowing manes of hair that can be seen from a considerable distance.

Summarizing a conversation he had about the creative impulse:

People tend to think that creative work is an expression of a preexisting desire or passion, a feeling made manifest, and in a way it is. As if an overwhelming anger, love, pain, or longing fills the artist or composer, as it might with any of us—the difference being that the creative artist then has no choice but to express those feelings through his or her given creative medium. I proposed that more often the work is a kind of tool that discovers and brings to light that emotional muck. Singers (and possibly listeners of music too) when they write or perform a song don’t so much bring to the work already formed emotions, ideas, and feelings as much as they use the act of singing as a device that reproduces and dredges them up.

In a later part, in the London section, he talks about a new wave of appreciation for the late artist Alice Neel, and touches on the convoluted ways we evaluate and reflect on creative works new and old:

Maybe the work looks prescient? Maybe it looks prescient every decade or so, whenever a slew of younger artists do work that is vaguely similar to hers? In that way maybe she’s being used to validate the present, and in turn the present is being used to validate the past?

And lastly, on PowerPoint:

A slide talk, the context in which this software is used, is a form of contemporary theater—a kind of ritual theater that has developed in boardrooms and academia rather than on the Broadway stage. No one can deny that a talk is a performance, but again there is a pervasive myth of objectivity and neutrality to deal with. There is an unspoken prejudice at work in those corporate and academic “performance spaces”—that performing is acting and therefore it’s not “real”. Acknowledging a talk as a performance is therefore anathema.

I became impatient with the few Michael Chabon books I’ve tried, never finished one. And historically I have had little patience with memoir. So what do I do? I go pick up Michael Chabon’s new memoir, Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son. Good decision, it turns out.

On the title page there’s a spinner-type illustration like you’d see on a game board, with possible landing spots marked Hypocrisy, Sexuality, Innocence, Regret, Sincerity, Nostalgia, Experience, and Play. If I could oversimplify, it’s about the awesomeness and awkwardness of being a guy. Not “awesome” as in “cool” but “awesome” in the sense of actual awe, realizing as you grow older that you are part of a tradition that our entire half of the population all experiences. Luckily he’s not too cliché with the whole thing, in one section even going so far as to meditate on the clichédness of feeling like a cliché and turn it into something worthwhile.

Cup size, wires, padding, straps, clasps, the little flowers between the cups: You need a degree, a spec sheet. You need breasts. I don’t know what you need to truly understand brassieres, and what’s more, I don’t want to know. I’m sorry. Go ask your mother.

There you have it: the most flagrant cliché imaginable. As I utter it, I might as well reach for a trout lure, a socket wrench, the switch on my model train transformer. This may be the fundamental truth of parenthood: No matter how enlightened or well prepared you are by theory, principle, and the imperative not to repeat the mistakes of your own parents, you are no better a father or mother than the set of your own limitations permits you to be.

The essays cover things like being a brother, cooking, the man-purse, faking it when you’re in over your head, best friends, Jose Canseco, first love, failed love, fatherhood and more. Here’s a bit on marriage, from the excellent story The Hand on My Shoulder (which link takes you to Chabon reading it on NPR):

The meaning of divorce will elude us as long as we are blind to the meaning of marriage, as I think at the start we must all be. Marriage seems—at least it seemed to an absurdly young man in the summer of 1987, standing on the sun-drenched patio of an elegant house on Lake Washington—to be an activity, like chess or tennis or a rumba contest, that we embark upon in tandem while everyone who loves us stands around and hopes for the best. We have no inkling of the fervor of their hope, nor of the ways in which our marriage, that collective endeavor, will be constructed from and burdened with their love.

Yesterday I tumbled a great quote from his essay on the The Wilderness of Childhood. Here’s another:

We have this idea of armchair traveling, of the reader who seeks in the pages of a ripping yarn or a memoir of polar exploration the kind of heroism and danger, in unknown, half-legendary lands, that he or she could never hope to find in life.

This is a mistaken notion, in my view. People read stories of adventure—and write them—because they have themselves been adventurers. Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity.

In “Cosmodemonic” he talks about being a “little shit” and basically, growing up:

We are accustomed to repeating the cliché, and to believing, that “our most precious resource is our children.” But we have plenty of children to go around, God knows, and as with Doritos, we can always make more. The true scarcity we face is of practicing adults, of people who know how marginal, how fragile, how finite their lives and their stories and their ambitions really are but who find value in this knowledge, even a sense of strange comfort, because they know their condition is universal, is shared.

Tyler Cowen said “This supposed paean to family life collapses quickly into narcissism, but that’s in fact what makes it work.” Much better than I’d expected.