How are the sidewalks? […] What kind of pollution?

Tag: Economics

How Americans pretend to love ‘ethnic food’

Despite all this talk about how we eat everything and like everything, we are not willing to pay for everything at the same rate, and that tells you something.

The Weird Global Appeal of Heavy Metal

The explosion of local bands around the world tends to track rising living standards and Internet use. Making loud music is expensive: You need electric guitars, amplifiers, speakers, music venues and more leisure time. “When economic development happens, metal scenes appear. They’re like mushrooms after the rain,” says Roy Doron, an African history professor at Winston-Salem State University.

Haven’t seen the whole fireside chat, but had to dig up the source when came across this great Jeff Bezos wisdom around 4.5 minutes in, on anticipating future business needs:

I very frequently get the question, “What’s going to change in the next ten years?” And that is a very interesting question. It’s a very common one. I almost never get the question, “What’s not going to change in the next ten years?” And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two. Because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices. And I know that’s going to be true ten years from now. They want fast delivery. They want vast selection. It’s impossible to imagine a future ten years from now where a customer comes up and says, “Jeff, I love Amazon. I just wish the prices were a little higher”. “I love Amazon. I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.” Impossible. And so the effort we put into those things, spinning those things up… we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying off dividends for our customers ten years from now. When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

There’s a life metaphor in there somewhere.

Unless You Are Spock, Irrelevant Things Matter in Economic Behavior

Rationally, no one should be happier about a score of 96 out of 137 (70 percent) than 72 out of 100, but my students were. And by realizing this, I was able to set the kind of exam I wanted but still keep the students from grumbling.

Unless You Are Spock, Irrelevant Things Matter in Economic Behavior

Peter Thiel on the Future of Innovation

Good stuff here. I appreciate the range and pace. It’s a little bit obnoxious, too, but better that than boring.

TYLER COWEN: It’s like Beach Boys music. Sounds optimistic on the surface but it’s deeply sad and melancholy.

And also:

PETER THIEL: I remember a professor once told me back in the ’80s that writing a book was more dangerous than having a child because you could always disown a child if it turned out badly.

And also:

PETER THIEL: I think often the smarter people are more prone to trendy, fashionable thinking because they can pick up on things, they can pick up on cues more easily, and so they’re even more trapped by it than people of average ability.

Etc.

Shitphone: A Love Story

One of the lesser-appreciated joys of online shopping is that, in the process of streamlining and compressing the expressions of capitalism we call “retail,” it gives us a god’s eye view of market patterns. In one search on Amazon or Newegg you can see a category’s past, present, and near future: high-margin luxury options on one side, low-margin or out-of-date good-enough options from unlikely or unknown brands on the other. Then, in the big mushy middle, brands fighting over a diminishing opportunity. This is faintly empowering. To watch the compressed cycles of modern consumer electronics pass through your viewfinder gives a calming order to an industry that depends on the perception that it is perpetually exceptional. This perspective also helps to enforce realism about your relationship with consumer electronics. Whether you choose the luxury option, the commodity option, or something in between, you are buying future garbage.

The invisible network that keeps the world running – BBC – Future.

To find out more about this huge, invisible network, I accompanied a group of architects and designers called the Unknown Fields Division for a rare voyage on a container ship between Korea and China. The aim of the trip was to follow the supply chain back to some of the remotest parts of China and the source of our consumer goods – and what we saw as we travelled through mega-ports and across oceans looked closer to science fiction than reality.

If I ever change to a new career it just might be container shipping.

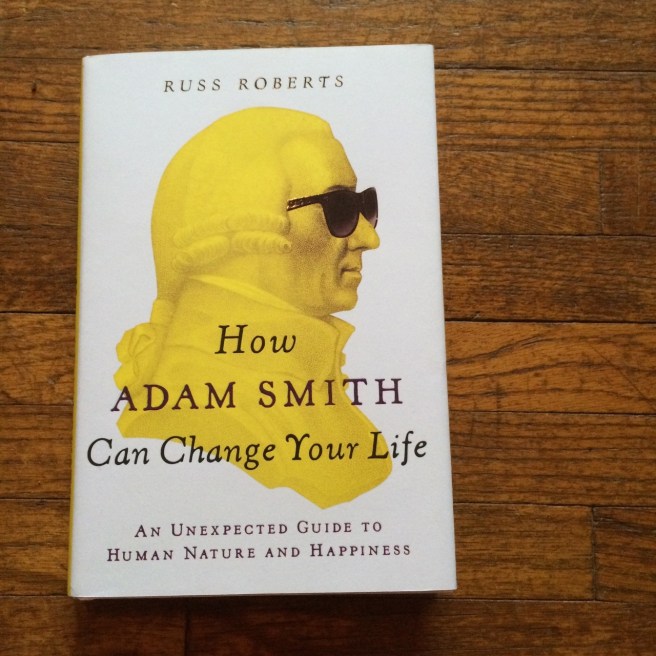

How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life

I read Russ Roberts’ book How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, and it’s certainly the most heavily dog-eared book I’ve read in the last couple months. It’s slighter in hindsight, but still got some good stuff out of it. Smith is best known for the more macro-level, distant, impersonal view on economics in The Wealth of Nations. This books relies on Smith’s lesser-known A Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explores the more intimate, direct relationships between individuals.

What I like is its undercurrent of humility and courtesy, for one, and the idea of ripple effects that go beyond us. There’s the idea of the “impartial spectator” in here – a hypothetical (and likely impossible) imagined outsider, an objective witness we can turn to to evaluate what we do. Of course, we’re delusional and biased and self-obsesssed. The principle stands, though, and the community around us helps to shape this hypothetical ideal that we imagine.

Virtuous behavior is like passable writing vs. great writing. At a basic level, there is grammar and syntax. There’s broad agreement on many of those details. But there’s a special something that goes beyond the basic requirements. Along the same lines, no one individual really decides what proper grammar is, and how a language works. But many people, making many small decisions every day, spread and sustain behaviors that add up to something bigger on the scale of family, office, neighborhood, nation, culture. And it’s that big-picture thinking that (hopefully) motivates us to “be lovely even when we can get away with not being lovely”. Going along with that are some healthy warnings about our obessions with powerful people, and about hubris when it comes to societal engineering.

Some other parts I like? Smith on keeping it simple:

What can be added to the happiness of the man who is in health, out of debt, and has a clear conscience?

Smith on praise we haven’t earned…

To us they [his praises] should be more mortifying than any censure, and should perpetually call to our minds, the most humbling of all reflections, the reflection of what we ought to be, but what we are not.

Or as Roberts phrases it, “Undeserved praise is a repimand – a reminder of what I could be.”

There’s another great section that talks about how gadgets are seductive. Roberts says, “We often care more about the elegance of the device than for what it can achieve.” Smith’s line here made me think about the tech and especially the #EDC community:

How many people ruin themselves by laying out money on trinkets of frivolous utility? What pleases these lovers of toys is not so much the utility, as the aptness of the machines which are fitted to promote it. All their pockets are stuffed with little conveniences.

Smith on why friendship is so valuable when you’re grieving – we see our pain through their eyes, and see it’s not so bad:

We are immediately put in mind of the light in which he will view our situation, and we begin to view it ourselves in the same light; for the effect of sympathy is instantaneous.

Roberts on caring on a smaller scale than save-the-world dreams:

Maybe, just maybe, your best way of making the world a better place is to be a really superlative husband or mom or neighbor. […] We forget that being good at our work helps others and makes the world a better place, too.

And a lovely bit of rabbinic wisdom:

It is not up to you to finish the work. But you are not free to desist from it.

A similar, more energetic book along the same lines is Sarah Bakewell’s very excellent How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer.

The New Canon – The LARB Blog

Through this reliance on Netflix, I’ve seen a new television pantheon begin to take form: there’s what’s streaming on Netflix, and then there’s everything else.

When I ask a student what they’re watching, the answers are varied: Friday Night Lights, Scandal, It’s Always Sunny, The League, Breaking Bad, Luther, Downton Abbey, Sherlock, Arrested Development, The Walking Dead, Pretty Little Liars, Weeds, Freaks & Geeks, The L Word, Twin Peaks, Archer, Louie, Portlandia. What all these shows have in common, however, is that they’re all available, in full, on Netflix.

Things that they haven’t watched? The Wire. Deadwood. Veronica Mars, Rome, Six Feet Under, The Sopranos. Even Sex in the City.

It’s not that they don’t want to watch these shows — it’s that with so much out there, including so much so-called “quality” programs, such as Twin Peaks and Freaks & Geeks, to catch up on, why watch something that’s not on Netflix? Why work that hard when there’s something this easy — and arguably just as good or important — right in front of you?

Markets influence taste.

Africa’s Trauma Epidemic

Billions of dollars have poured into the continent to fight killer diseases. But the most basic killer, injury, is neglected.

I have never once thought about this before.

Who Will Prosper in the New World – NYTimes.com

A lot of jobs will consist of making people feel either very good or very bad about themselves.

In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters – NYTimes.com.

All else being equal, upward mobility tended to be higher in metropolitan areas where poor families were more dispersed among mixed-income neighborhoods. Income mobility was also higher in areas with more two-parent households, better elementary schools and high schools, and more civic engagement, including membership in religious and community groups.

Hey wait that cuts across party lines what should I believe?! Cf. The Geography of Stuck.

The Cookbook Theory of Economics – By Tyler Cowen | Foreign Policy. Cookbooks as a proxy for economic development…

Soon it will be possible to cook the dishes of the entire world, but only those, alas, that survive the process of commercialization and standardization.

Why are we not much, much, much better at parenting? | Practical Ethics

Economics!

Humans are quite bad at estimating the results of different interventions, if the feedback only comes years later. One needs only to see the plethora of different parenting guides and opposed schools of upbringing thought. Such variety couldn’t maintain itself if it were easy for parents to see which methods worked and which didn’t. Thus parents are poor at knowing what they need, and hence make ineffective consumers from the economic perspective.

Also, “a lot of parenting techniques are procedural, rather than declarative.”

Why are we not much, much, much better at parenting? | Practical Ethics

The Economics of Social Status

Status as currency. The whole thing is worth a read. I liked this aside on public speaking, which also connects with live music and standup comedy and other types of performance, and why they’re scary:

“Bidding for status” is another activity with economic characteristics. The nature of a bid is that it sets a particular ‘price’ that can be accepted or rejected. Robin Hanson suspects that speaking in public is a way of bidding for status. The very act of standing in front of a group and speaking authoritatively represents a claim to relatively high status. If you speak on behalf of the group – i.e., making statements that summarize the group’s position or commit the group to a course of action — then you’re claiming even higher status. These bids can either be accepted by the group (if they show approval or rapt attention, and let you continue to speak) or rejected (if they show disapproval, interrupt you, ignore you, or boo you off stage).

How The South Will Rise To Power Again | Newgeography.com

In the 1950s, the South, the Northeast and the Midwest each had about the same number of people. Today the region is almost as populous as the Northeast and the Midwest combined.

I did not know that, along with a lot of the other family and economic trends mentioned in the article. Filed under: the South.

Rebecca Solnit · Diary: Google Invades · LRB 7 February 2013

I loved this essay on San Francisco and boomtowns. Nicely done.

Rebecca Solnit · Diary: Google Invades · LRB 7 February 2013

What’s Better: Cell Phones or Indoor Toilets? – The Daily Beast

I’m not sure how revealing it is that people in rural China and Africa have chosen something that is relatively inexpensive and available, over something that is fairly expensive, and isn’t. Saying “Well, they didn’t install this totally inadequate substitute” doesn’t really persuade me.

Megan McArdle FTW.

What’s Better: Cell Phones or Indoor Toilets? – The Daily Beast

Cato Unbound » Why Online Education Works

Very interesting perspective. I like this bit on lectures and attention spans:

Online education can also break the artificial lecture length of 50–90 minutes. Many teaching experts say that adult attention span is 10–15 minutes in a lecture, with many suggesting that attention span has declined in the Internet era. A good professor can refocus the attention of motivated students over longer periods. Nevertheless, it is clear that the standard lecture length has not been determined by optimal learning time but by the high fixed costs of traveling to school. Lower the fixed costs and lectures will evolve to a more natural level, probably between 5–20 minutes of length—perhaps not coincidentally the natural length of a lecture is probably not that different from the length of a typical popular music track or television segment.