Ray Lewis visits Elon Football Team. Inspirational Speech. The thunder is a nice touch.

When you wake up in the mornings, don’t let your alarm clock be the only thing that wakes you up.

Ray Lewis visits Elon Football Team. Inspirational Speech. The thunder is a nice touch.

When you wake up in the mornings, don’t let your alarm clock be the only thing that wakes you up.

Supply of Per Capita Football Talent.

This chart comes from a paper presented by Theodore Goudge, an associate professor in the department of geography at Northwest Missouri State University, at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers. It pretty clearly shows what Goudge referred to as the “pigskin cult” of the south.

The paper in question is “The Geography of College Football Player Origins & Success: Football Championship Subdivision (FCS)”, here’s an abstract. Featured in On Urban Meyer’s Ohio State, Wisconsin, and the Big Ten expanding to include Maryland and Rutgers – Grantland.

Warrior. Some plot points are about subtle as a kick to the head, but the power is there, too. Much, much better than I expected, thanks to a great cast (A.O. Scott: “These are tough guys, but you can only care about them if you believe that they can break.”) and a great pace. Ebert:

This is a rare fight movie in which we don’t want to see either fighter lose. That brings such complexity to the final showdown that hardly anything could top it — but something does.

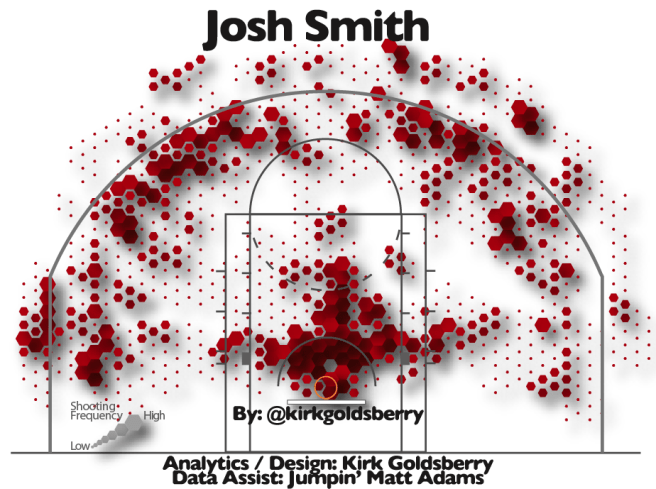

The Long Two and Josh Smith | CourtVision.

The reason Atlanta fans melt down when Josh shoots a jumper is dualistic: it’s a low-percentage shot AND he is a beast near the rim.

Ooooohhhh man do NOT get me started.

What happens when your neighbor is a multimillion dollar shrine to sports

Thomas Wheatley bringin’ truth to the people.

James has always been harder to place. On the court, he’s a whole anthology of players: an oversize, creative point guard like Magic Johnson; a bodybuilder-style space-displacer like Karl Malone; a harassing, omnipresent defender like Scottie Pippen; a leaping finisher like Dr. J. He does everything that a human can possibly do on a basketball court; he is 12 different specialists fused, Voltron-style, into a one-man All-Star team.

Somehow this doesn’t quite track. Even as we admire James’s unique skill set, we’re always forced to think about the tension that holds all of the disparate parts together — the contradictory philosophies of the game that all of those different skills imply.

Do I stop? Or go?

“THE IRON LEG”

Dirk Nowitzki showed the world his step back jumper. Kobe Bryant watched Dirk win the 2010-2011 NBA Championship. Now, Kobe shoots Dirk’s step back jumper.

Some people might slight Bryant for so clearly jacking “The Iron Leg.” Not me. I think it’s incredible. And awesome.

Dirk created the best post-Olajuwon post move in basketball, Kobe understood it’s value, and put it in his game. That’s why he’s great — anything to get better. Last night, Bryant used it in the Playoffs.

You know, imitation is the highest form of flattery, but before you go thinking Kobe’s handing out compliments…

“I improved his move. I can shoot mine from the three-point line. He can’t do that… Dirk does it well, I do it better. Mine’s a little sexier.”

-Kobe Bryant

What, after all, are reality TV shows except an effort to reproduce the drama and unexpected turns of sports?

Reblogging so I can enjoy this phrase a little longer: “Oklahoma City’s free-jazz marionette of a superstar and its hailstorm of a point guard”.

Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook, and a midseason report on the Oklahoma City Thunder – Grantland

NBA Rookie Midterm Report. I love these radar charts for sports, especially with percentile rankings. Awesome.

Kobe’s relentlessness has always been his most celebrated quality, but this season, he’s starting to remind me of one of those space probes that somehow keep feeding back data even after they’ve gone out twice as far as the zone where they were supposed to break down. You know these stories — no one at NASA can believe it, every day they come into work expecting the line to be dead, but somehow, the beeps and blorps keep coming through. Maybe half the transmissions get lost these days, or break up around the moons of Jupiter, but somehow, this piece of isolated metal keeps functioning on a cold fringe of the solar system that no human eyes have seen.

That’s Kobe, right? While the rest of the Lakers look increasingly anxious and time-bound, he just keeps gliding farther out, like some kind of experiment to see whether never having a single feeling can make you immortal. He’s barely preserving radio contact with anyone else at this point, but basketball scientists who’ve seen fragments of his diagnostic readouts report that the numbers are heartening. It’s bizarre.

(Image via Prospect Magazine)

The Joy of Tennis

With the Australian Open coming to a record-breaking, excessively long climax this weekend, what better to fill the tennis void than some great writing on the subject?

- The correct way to begin a tour of tennis writing is with David Foster Wallace. In his 1996 essay for Esquire, he uses a profile of Michael Joyce as a cover for an obsessive and effortlessly insightful consideration of tennis. Quite likely the best tennis nonfiction written to date. He revisits tennis ten years later for the New York Times and lets his inner fanboy loose with an equally epic and insightful profile of Roger Federer.

- Three years later, Cynthia Gorney gives us a fantastic, sprawling profile of Rafael Nadal.

- Rounding out the profiles of today’s top tennis players is S.L. Price with a profile of Novak Djokovic and Sarah Corbett on Venus Williams.

- For profiles of yesterday’s best, Julian Rubenstein’s award-winning profile of John McEnroe and Frank Deford’s 1978 profile of Jimmy Connors are required reading.

- One of the great pleasures of tennis is the personalities and the rivalries, and as Gerald Marzorati pointed out last year, “rivalries in tennis are like no others in sports.” In recent years, we’ve seen the same three — four or five if you’re generous — players constantly jockeying for the top spots in the rankings, always climaxing in thrilling, suspenseful, and often record-breaking semi-final and final matches in the year’s tournaments. “To be a great tennis player is to need a rival.”

- Although you wouldn’t call them rivals, John Isner and Nicolas Mahut found themselves locked in a seemingly neverending first round match-up at last year’s Wimbledon. Most tennis matches end long before the 11 hours this one took to end, usually because a player loses concentration, but neither Mahut or Isner blinked for 3 days of play, and Ed Caesar explains why in his GQ piece following the match.

- In “The most beautful game,” Geoff Dyer considers the beauty of tennis. It’s not enough that the players are simply good at tennis — everything you see on Centre Court at Wimbledon can be “replicated by an average player in a park.” The draw for the viewing public, he thinks, is wrapped up in the mechanics of the game: the most effective way to play is gracefully, as best exempified by Federer’s memorable single-handed backhand.

Read these and then read John McPhee’s Levels of the Game (part II) [$], and you’ll have just about covered all of the best writing on tennis.

He took the burden of history, carefully placed it in the garbage, and lit the garbage on fire.

I just thought that was a nice turn of phrase.

One of the fundamental aspects missing in today’s game is the ability for players (of any position) to work hard to get good spots on the floor (For post-up opportunities, that usually means getting at least one foot in the paint on a post catch). Contrary to popular opinion, this isn’t always derived from laziness. In fact, most times it’s because players are so used to being so much taller/stronger/more athletic than their competition, that they haven’t yet realized the value of getting prime real estate.

Pete Beatty (@nocoastoffense) sums it up: “In which @kylebeachy invents skateboard crit”.

You’re Not Me: Nyjah Huston and Inflationary Spectacle | The Classical

Corresponding to the umpire-as-instrument idea is External Realism. According to External Realism, there are umpiring-independent facts of the game — balls are really fair or foul, runners are either safe or out — and the questions we face are merely epistemological, how best to determine the facts, how to find out.

Corresponding to the umpire-as-player idea is Internal Anti-Realism. According to Internal Anti-Realism, umpires don’t call them as they see them; umpires, through their calls, make it the case that a pitch is a strike or a ball, a runner safe or out. There are no umpire-independent facts in baseball.

Those who decry statistics are often the first to cite a statistic with a sample size of exactly one.

One nice thing about sportswriting about the greats is that it can point you to things you didn’t get to experience live. I’d never seen the McEnroe-Borg tie break in the 4th set of the 1980 Wimbledon Final. Incredible.