I read an interview with Tom Waits, around the time of his album “Rain Dogs,” in which he talked about how you come to a point on an instrument where you have to stop playing it and find another instrument that you don’t know what you’re doing with. Part of songwriting is having that naïve excitement about not quite realizing why you’re getting off on it, because you haven’t had time to pull it apart yet. Songwriting relies on not pulling things apart: the best ideas are the simple ideas.

Tag: newyorker

Purloined Letters: Are we too quick to denounce plagiarism?

A brief essay James R. Kincaid in The New Yorker, January 20, 1997. I like this bit, quoting Helen Keller:

It is certain that I cannot always distinguish my own thoughts from those I read, because what I read becomes the very substance and text of my mind.

That’s found in her autobiography, where she goes on to say:

Consequently, in nearly all that I write, I produce something which very much resembles the crazy patchwork I used to make when I first learned to sew. This patchwork was made of all sorts of odds and ends–pretty bits of silk and velvet; but the coarse pieces that were not pleasant to touch always predominated. Likewise my compositions are made up of crude notions of my own, inlaid with the brighter thoughts and riper opinions of the authors I have read. It seems to me that the great difficulty of writing is to make the language of the educated mind express our confused ideas, half feelings, half thoughts, when we are little more than bundles of instinctive tendencies. Trying to write is very much like trying to put a Chinese puzzle together. We have a pattern in mind which we wish to work out in words; but the words will not fit the spaces, or, if they do, they will not match the design. But we keep on trying because we know that others have succeeded, and we are not willing to acknowledge defeat.

A Cruel Country by Roland Barthes : The New Yorker

“Journal excerpts by Roland Barthes about mourning his mother, Henriette, who died at eighty-four, in October, 1977.” It’s a real shame this one is behind a paywall. Favorite bits:

What I find utterly terrifying is mourning’s discontinuous character.

And:

Mourning: not a crushing oppression, a jamming (which would suppose a “refill”), but a painful availability: I am vigilant, expectant, awaiting the onset of a “sense of life”.

And also:

1st mourning

false liberty

2nd mourning

desolate liberty

deadly, without

worthy occupation

Trekking Midtown by Tad Friend : The New Yorker

This week’s issue has been pretty darn good so far. “The goal: to walk from the Empire State Building, on West Thirty-third Street, to Rockefeller Center, on West Forty-eighth, without ever setting foot on Fifth or Sixth Avenue.”

This is pretty much perfect. See also the wisdom of Communicatrix: “Family. Friends. Health. Work. Pick any three.”

Painkiller Deathstreak: Adventures in video games

I like this kind of essay. The dude had never played video games before! I wish he’d chosen a broader variety of games, but it’s nice to have a fresh perspective. You take a lot of this for granted when you grow up with it:

The second thing I learned about video games is that they are long. So, so long. Playing one game is not like watching one ninety-minute movie; it’s like watching one whole season of a TV show—and watching it in a state of staring, jaw-clenched concentration. If you’re good, it might take you fifteen hours to play through a typical game. If you’re not good, like me, and you do a fair amount of bumping into walls and jumping place when you’re under attack, it will take more than twice that.

If you aren’t having no fun, die, because you’re running a worthless program, far as I’m concerned.

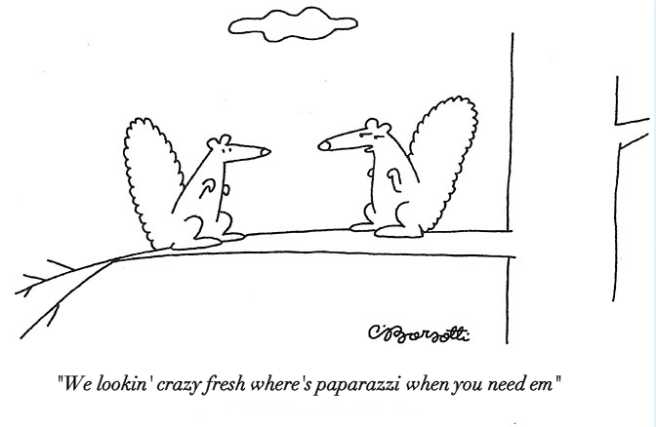

Kanye West’s tweets meet The New Yorker’s Cartoon Caption Contest. The results are hilarious!

Thanks Josh A. Cagan (@joshacagan on Twitter) for these amazing mash-ups – you made our morning!

Asterisks, like footnotes, can be more distracting than clarifying, because they hint at a completeness to the story that a wise reader wouldn’t otherwise think to presume.

The Ice Balloon – S. A. Andrée’s North Pole balloon expedition : The New Yorker. I wish this weren’t behind a paywall, because non-subscribers are missing out on a wonderful piece of writing. (Photo of the fallen balloon by Nils Strindberg, from the Grenna Museum.)

If you are feeling nervous, nervous is good. All right? It makes us stop thinking about things. It makes us ready to play. If you’re nervous, that’s fine. Feel nervous.

Out of the West: Clint Eastwood’s shifting landscape by David Denby for The New Yorker. My relatively new Eastwood obsession means of course I dropped everything to read it. Lots of good stuff in this article.

Top Ten Glissandos

Sorry about the couple photo-less posts in a row, but you have to hear this: Alex Ross’s “Top Ten Glissandos.”

For maximum effect, press all the buttons in quick succession.

(via Unquiet Thoughts)

This is delightful. Might I also suggest The Beatles’ A Day In the Life?

Postscript: J. D. Salinger – The New Yorker

Archive of Salinger’s stories for the New Yorker. (via)

Unquiet Thoughts

Alex Ross’ new music blog on the New Yorker website. Nice counterweight to the blog of Sasha Frere-Jones .

We had a few complaints that the MP3s of our last record wasn’t encoded at a high enough rate. Some even suggested we should have used FLACs, but if you even know what one of those is, and have strong opinions on them, you’re already lost to the world of high fidelity and have probably spent far too much money on your speaker-stands.

You care about things that you make, and that makes it easier to care about things that other people make.

Marshmallows and time preference

You probably recall Jonah Lehrer’s New Yorker article about the kids who were told not to eat the marshmallow. Those who were able to hold out were better behaved, higher achievers later in life.

Low delayers, the children who rang the bell quickly, seemed more likely to have behavioral problems, both in school and at home. They got lower S.A.T. scores. They struggled in stressful situations, often had trouble paying attention, and found it difficult to maintain friendships. The child who could wait fifteen minutes had an S.A.T. score that was, on average, two hundred and ten points higher than that of the kid who could wait only thirty seconds.

When I was reading it, it reminded me of some ideas that have been around for in economics for a couple centuries or so: time preference and intertemporal choice. Someone with high time preference will tend to consume sooner rather than later. People with low time preference are the savers—the ones who can hold out. The same applies to social groups or societies. For example, married folks or people who have children (or expect them) tend to have lower time preference and set aside more for the future. And they tend to display fewer risky behaviors, so they can actually see the eventual benefits of their saving. It’s the opposite for the single, childless, young. This relates to why single males in their 20s tend to have high car insurance, lots of cool electronics stuff, and little in their IRAs. Consume more now, have less later.

“It’s worth knowing about ten times as much as you ever use, so you can move freely.”—Ian McEwan

New Yorker profile of Will Oldham, whose music I’ve grown to love love love over the past year or so.