This is pretty much perfect. See also the wisdom of Communicatrix: “Family. Friends. Health. Work. Pick any three.”

This is pretty much perfect. See also the wisdom of Communicatrix: “Family. Friends. Health. Work. Pick any three.”

The person leading the Well-Planned Life emphasizes individual agency, and asks, “What should I do?” The person leading the Summoned Life emphasizes the context, and asks, “What are my circumstances asking me to do?”

(via)

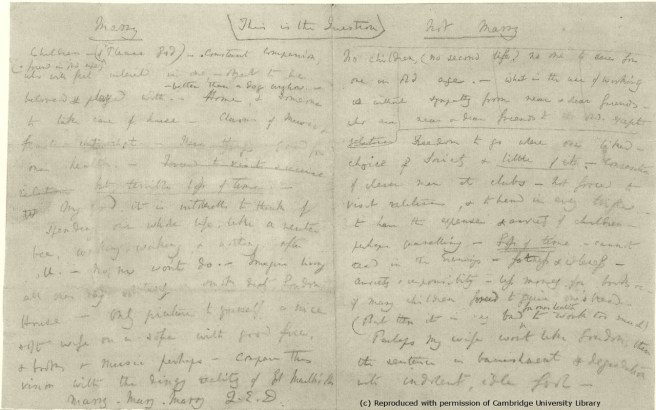

This is the Question, Charles Darwin writes at the top of the page. Each half of the page is a list brainstorming his two options with Emma Wedgewood:

To Marry…

Children — (if it Please God) — Constant companion, (& friend in old age) who will feel interested in one, — object to be beloved & played with. — —better than a dog anyhow. — Home, & someone to take care of house — Charms of music & female chit-chat. — These things good for one’s health. — Forced to visit & receive relations but terrible loss of time. —

My God, it is intolerable to think of spending ones whole life, like a neuter bee, working, working, & nothing after all. — No, no won’t do. — Imagine living all one’s day solitarily in smoky dirty London House. — Only picture to yourself a nice soft wife on a sofa with good fire, & books & music perhaps — Compare this vision with the dingy reality of Grt. Marlbro’ St.

or Not Marry?

No children, (no second life), no one to care for one in old age.— What is the use of working without sympathy from near & dear friends—who are near & dear friends to the old, except relatives

Freedom to go where one liked — choice of Society & little of it. — Conversation of clever men at clubs — Not forced to visit relatives, & to bend in every trifle. — to have the expense & anxiety of children — perhaps quarelling — Loss of time. — cannot read in the Evenings — fatness & idleness — Anxiety & responsibility — less money for books &c — if many children forced to gain one’s bread. — (But then it is very bad for ones health to work too much)

Perhaps my wife wont like London; then the sentence is banishment & degradation into indolent, idle fool —

The final result:

Marry — Marry — Marry. Q.E.D.

He also goes on to wrestle with the question of marrying sooner vs. later. (via)

See also: lay it all out where you can look at it.

If you study the root causes of business disasters, over and over you’ll find this predisposition toward endeavors that offer immediate gratification. If you look at personal lives through that lens, you’ll see the same stunning and sobering pattern: people allocating fewer and fewer resources to the things they would have once said mattered most.

Family. Friends. Health. Work. Pick any three.

College is such an amazing time of freedom. For many of you, this is the first time in your life when it’s completely up to you, and you alone, to decide what you study, what activities you engage in, and how you structure your day. One idea I came up with as an undergrad was to try to maintain balance by making sure I engaged in four different types of activities every single day. These were:

-something intellectual (not so difficult at school);

-something physical (like running, biking, a team sport);

-something creative (like music, art, or writing); and

-something social (like lunch with a friend).

College and the Art of Life – David Salesin, Convocation Address, 28 September 2003

Forgot to share this a while back. (via)

Me, tweetin’ earlier this evening:

And I went on to remind myself: “Gotta be constantly tweaking the recipe, right? I kinda know the ingredients but the ratios get out of whack”. I say all this because it reminded me of something that I bookmarked a couple months ago and forgot to share, which is Seth Roberts on Optimal Daily Experience (via Justin Wehr):

Everyone knows about RDAs (Recommended Daily Allowances) of various nutrients. In a speech to new University of Washington students, David Salesin, a computer scientist, advised them to “maintain balance” by getting certain experiences daily:

something intellectual [such as a computer science class] (not so hard in college); something physical (like running, biking, a team sport); something creative (like music, art, or writing); and something social (like lunch with a friend). This served him well in college, he said, and he continued it after college.

Roberts goes on to propose his own list. This isn’t rocket surgery. Make some basic priorities, try to check them off on a regular basis, re-evaluate every so often. So I think to myself, how simple would it be to take a basic calendar, divide each day into four quadrants for these four, and add a little check marks as appropriate so you can track yourself? Very simple. Done.

It also kinda ties in with Austin Kleon’s tumble about Ben Franklin and pros and cons lists. Says Ben:

And tho’ the Weight of Reasons cannot be taken with the Precision of Algebraic Quantities, yet when each is thus considered separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less likely to take a rash Step; and in fact I have found great Advantage from this kind of Equation, in what may be called Moral or Prudential Algebra.

First off, I love the phrase “Moral or Prudential Algebra”. It ties in with my general attitude of 19th-century optimism (which phrase I stole for my Twitter bio), the idea that with a little forethought and pluck and some striving, you can make Good Life Decisions. And secondly, there’s that idea that you should lay it all out where you can look at it–and this is not just for quote creative unquote stuff. The point is, your life is the Ultimate Creative Project, if you will, so you’d best keep an eye on the how the stuff’s accumulating. Not the details themselves, but the pattern, the trend. To quote Colin Marshall again:

Satisfaction is a product not of where you are, but of where you’re going. To get calculistic, it ain’t about your value, it’s about your first derivative (and maybe your second). In this light, statements like “When x happens, I’ll attain happiness” don’t make sense, but ones like “While x is happening, I’ll be happy” make somewhat more.

And a bit later in the evening I was reading Derek Sivers’ excellent notes on The Happiness Hypothesis (in the bookpile now) and I came across a couple quotes that tie in with Roberts, Salesin, and Franklin. First on moral education:

Moral education must also impart tacit knowledge – skills of social perception and social emotion so finely tuned that one automatically feels the right thing in each situation, knows the right thing to do, and then wants to do it. Morality, for the ancients, was a kind of practical wisdom.

and then on choices vs. conditions:

Voluntary activities, on the other hand, are the things that you choose to do, such as meditation, exercise, learning a new skill, or taking a vacation. Because such activities must be chosen, and because most of them take effort and attention, they can’t just disappear from your awareness the way conditions can. Voluntary activities, therefore, offer much greater promise for increasing happiness while avoiding adaptation effects.

Note to self: moral education (not just ethics stuff, but we’re venturing into Franklin’s thirteen virtues here) involves a set of skills that you can practice. Practice and it becomes voluntary, habitual, sustaining. That’s my working theory, in any case. So what have I learned today? Pay attention. Make good choices. Nail the basics, consistently. Basically, the most vague, mundane things ever, but sometimes having a new sense of the gestalt of the whole endeavor can be very refreshing.

The life I have chosen gives me my full hours of enjoyment for the balance of my life. The Sun will not rise, or set, without my notice, and thanks.

Personally and emotionally it surprised me that I could actually stay committed to something so consuming without ruining my life. It’s almost axiomatic that people in the arts have to be willing to jettison their friends, marriages, loves, in order to really push through and break out. That is a hefty quantity of bullshit, and is an excuse for not living a full life and integrating work into it. This more than anything was the most positive outcome for me.

One of the things I wish more people (anyone) would blog about is not just the books, movies, blog posts, or magazine articles they liked, but rather what in their estimation were the best uses of their time. Was it a chapter of a book or a particular article from the New York Times? Beyond just the content they consumed, was it maybe a conversation with a friend?

Satisfaction is a product not of where you are, but of where you’re going. To get calculistic, it ain’t about your value, it’s about your first derivative (and maybe your second). In this light, statements like “When x happens, I’ll attain happiness” don’t make sense, but ones like “While x is happening, I’ll be happy” make somewhat more.

Do more, buy less…

We found that participants were less satisfied with their material purchases because they were more likely to ruminate about unchosen options (Study 1); that participants tended to maximize when selecting material goods and satisfice when selecting experiences (Study 2); that participants examined unchosen material purchases more than unchosen experiential purchases (Study 3); and that, relative to experiences, participants’ satisfaction with their material possessions was undermined more by comparisons to other available options (Studies 4 and 5A), to the same option at a different price (Studies 5B and 6), and to the purchases of other individuals (Study 5C). Our results suggest that experiential purchase decisions are easier to make and more conducive to well-being.

More here [pdf]. (via)

The relative relativity of material and experiential purchases

My favorite: “Don’t expect to be too happy, that is counterproductive.”

“The heuristics on this list are easily memorable and implementable life problem-solving strategies — "quick and dirty” ones, if you like — that I’ve drawn from experience which, even if they prove shaky in border cases, still work most of the time.“

I kept a regular journal on this recent vacation, as I did so diligently on previous long hikes and last year’s trip to Iceland. This was a lazier trip than I’d ever done, so I wrote more than ever before. I may have have more to say about travel in general and and some Nicaraguan sites I saw in later posts, but here are some things that struck me…

And a few other amusing events:

A book needn’t be an author’s life work; a squib of novel insight with supporting evidence is sufficient. If you are going to have something be your life’s work, let it be a book of your life’s wisdom. Some people have 300 page books devoted to trivial topics and blog posts devoted to their life’s wisdom; that seems ironic to me.

I became impatient with the few Michael Chabon books I’ve tried, never finished one. And historically I have had little patience with memoir. So what do I do? I go pick up Michael Chabon’s new memoir, Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son. Good decision, it turns out.

On the title page there’s a spinner-type illustration like you’d see on a game board, with possible landing spots marked Hypocrisy, Sexuality, Innocence, Regret, Sincerity, Nostalgia, Experience, and Play. If I could oversimplify, it’s about the awesomeness and awkwardness of being a guy. Not “awesome” as in “cool” but “awesome” in the sense of actual awe, realizing as you grow older that you are part of a tradition that our entire half of the population all experiences. Luckily he’s not too cliché with the whole thing, in one section even going so far as to meditate on the clichédness of feeling like a cliché and turn it into something worthwhile.

Cup size, wires, padding, straps, clasps, the little flowers between the cups: You need a degree, a spec sheet. You need breasts. I don’t know what you need to truly understand brassieres, and what’s more, I don’t want to know. I’m sorry. Go ask your mother.

There you have it: the most flagrant cliché imaginable. As I utter it, I might as well reach for a trout lure, a socket wrench, the switch on my model train transformer. This may be the fundamental truth of parenthood: No matter how enlightened or well prepared you are by theory, principle, and the imperative not to repeat the mistakes of your own parents, you are no better a father or mother than the set of your own limitations permits you to be.

The essays cover things like being a brother, cooking, the man-purse, faking it when you’re in over your head, best friends, Jose Canseco, first love, failed love, fatherhood and more. Here’s a bit on marriage, from the excellent story The Hand on My Shoulder (which link takes you to Chabon reading it on NPR):

The meaning of divorce will elude us as long as we are blind to the meaning of marriage, as I think at the start we must all be. Marriage seems—at least it seemed to an absurdly young man in the summer of 1987, standing on the sun-drenched patio of an elegant house on Lake Washington—to be an activity, like chess or tennis or a rumba contest, that we embark upon in tandem while everyone who loves us stands around and hopes for the best. We have no inkling of the fervor of their hope, nor of the ways in which our marriage, that collective endeavor, will be constructed from and burdened with their love.

Yesterday I tumbled a great quote from his essay on the The Wilderness of Childhood. Here’s another:

We have this idea of armchair traveling, of the reader who seeks in the pages of a ripping yarn or a memoir of polar exploration the kind of heroism and danger, in unknown, half-legendary lands, that he or she could never hope to find in life.

This is a mistaken notion, in my view. People read stories of adventure—and write them—because they have themselves been adventurers. Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity.

In “Cosmodemonic” he talks about being a “little shit” and basically, growing up:

We are accustomed to repeating the cliché, and to believing, that “our most precious resource is our children.” But we have plenty of children to go around, God knows, and as with Doritos, we can always make more. The true scarcity we face is of practicing adults, of people who know how marginal, how fragile, how finite their lives and their stories and their ambitions really are but who find value in this knowledge, even a sense of strange comfort, because they know their condition is universal, is shared.

Tyler Cowen said “This supposed paean to family life collapses quickly into narcissism, but that’s in fact what makes it work.” Much better than I’d expected.