Technology is fairly good at controlling external reality to promote real biological fitness, but it’s even better at delivering fake fitness—subjective cues of survival and reproduction without the real-world effects.

Tag: culture

I’m not terribly interested in whether real, brain-chemically-defined Asperger’s is over- or underdiagnosed, or whether it exists at all except as a metaphor. I’m interested in how vital the description feels lately. Is there any chance the Aspergerian retreat from affective risk, in favor of the role of alienated scientist-observer, might be an increasingly “popular” coping stance in a world where corporations, machines, and products flourish within their own ungovernable systems?

A question of discrimination – AC Grayling on art and elitism | The Guardian

A mature culture is one which wishes to know more about other cultures, and which values the best examples of what it has of them, and which is better able to appreciate them because it has standards and insights developed in appreciation of its own.

It was the African figures in the Louvre that inspired Picasso. That one fact alone could serve to remind us how porous high culture is, in both directions, and how symbiotic the existence of all cultures is, especially in the globalised world. When receptive sensibilities engage with the artefacts of the past and other civilisations, they are nourished by them and learn from them, not least how to be discerning.

A question of discrimination – AC Grayling on art and elitism | The Guardian

The concert hall is one of the few places where we become unreachable, where we can switch off our lifelines and surrender to a form that will not let us go for an hour or more.

We erected one of the great cultural constructions of our times, the weekend, to make fun more culturally and institutionally available.

Whatever the subject, a real critic is a cultural critic, always: if your judgment doesn’t bring in more of the world than it shuts out, you shouldn’t start.

Eating Your Cultural Vegetables – NYTimes.com

Via David Hayes, who said it best:

There’s no single solid takeaway from this essay about the culture we feel obligated to consume, but I think it’s a good and valuable thing to think about and pay attention to.

If everyone had good manners we wouldn’t need laws. I think that’s the great hope of civility, that we can control society through cultural means rather than through lawyers.

n+1: Sad as Hell

Tabloids are only interesting as long as you’re always reading them; let your checkout-line-skimming lapse for a week and the thought of celebrity gossip seems pointless.

“Sunset Portraits, From 8,462,359 Sunset Pictures on Flickr, 12/21/10”. A photo illustration by Penelope Umbrico for The New York Times. I’ve probably become inured to news images, but this was one of those rare ones that stopped me in my tracks. If there were a print of this, I’d probably buy it. Cyberspace When You’re Dead.

‘I took my kids offline’ | The Guardian

Upon receipt of Maushart’s out-of-office email stating that she was no longer online, many of them assumed that she’d had a nervous breakdown.

‘I took my kids offline’ | The Guardian

Upon receipt of Maushart’s out-of-office email stating that she was no longer online, many of them assumed that she’d had a nervous breakdown.

SPIEGEL Interview with Umberto Eco

We have a limit, a very discouraging, humiliating limit: death. That’s why we like all the things that we assume have no limits and, therefore, no end. It’s a way of escaping thoughts about death. We like lists because we don’t want to die.

And also:

I was fascinated with Stendhal at 13 and with Thomas Mann at 15 and, at 16, I loved Chopin. Then I spent my life getting to know the rest. Right now, Chopin is at the very top once again. If you interact with things in your life, everything is constantly changing. And if nothing changes, you’re an idiot.

“Whenever I hear the word ‘culture’, I bring out my checkbook.”

Jean-Luc Godard’s crack is a variation on a line from Hanns Johst’s play Schlageter.

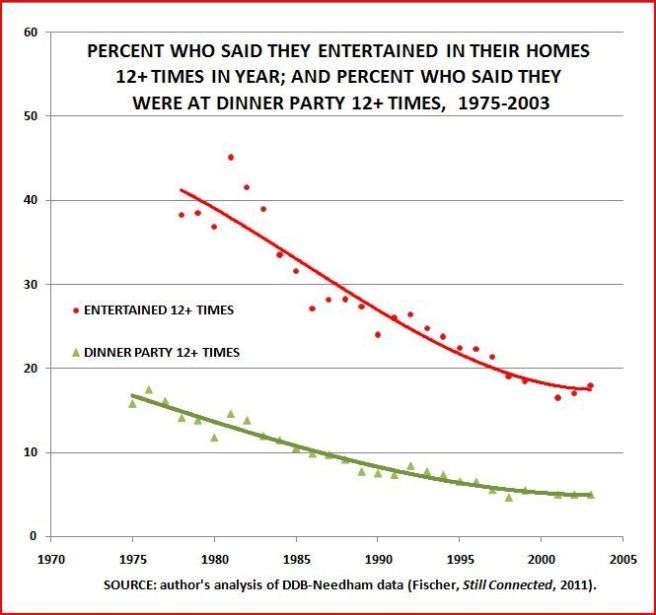

No Dinner Invitations? – Made in America. Suspected causes: both parents working, more commuting. But our socializing, in general, trends upward: more phone calls, texts, jaunts to restaurants, bars, etc.

So much more than the world could offer

From historian Daniel Boorstin’s introduction to The Image, his book from 1961:

When we pick up our newspaper at breakfast, we expect — we even demand — that it bring us momentous events since the night before. We turn on the car radio as we drive to work and expect “news” to have occurred since the morning newspaper went to press. Returning in the evening, we expect our house to not only shelter us, but to relax us, to dignify us, to encompass us with soft music and interesting hobbies, to be a playground, a theater, and a bar. We expect our two-week vacation to be romantic, exotic, cheap, and effortless. We expect a faraway atmosphere if we go to a nearby place; and we expect everything to be relaxing, sanitary, and Americanized if we go to a faraway place. We expect new heroes every season, a literary masterpiece every month, a dramatic spectacular every week, a rare sensation every night. We expect everybody to feel free to disagree, yet we expect everybody to be loyal, not to rock the boat or to take the Fifth Amendment. We expect everybody to believe deeply in his religion, yet not to think less of others for not believing. We expect our nation to be strong and great and vast and varied and prepared for every challenge; yet we expect our “national purpose” to be clear and simple, something that gives direction to the lives of nearly two hundred million people and yet can be bought in a paperback at the corner drugstore for a dollar.

We expect anything and everything. We expect the contradictory and the impossible. We expect compact cars which are spacious; luxurious cars which are economical. We expect to be rich and charitable, powerful and merciful, active and reflective, kind and competitive. We expect to be inspired by mediocre appeals for “excellence,” to be made literate by illiterate appeals for literacy. We expect to eat and stay thin, to be constantly on the move and ever more neighborly, to go to a “church of our choice” and yet feel its guiding power over us, to revere God and to be a God.

Never have people been more the masters of their environment. Yet never have people felt more deceived and disappointed. For never has a people expected so much more than the world could offer.

Up From Darkness – Book Review: “Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light” by Jane Brox – NYTimes.com

Who had light and who did not? What did different types of people do with their newfound hours? How did street lighting change public behavior? (Once drinkers could move safely between taverns, instead of perching on a single tavern stool all night … the streets became far rowdier; prostitutes previously confined to brothels could now sell their wares al fresco.) With increased mobility and safety, those who could afford lighting stayed up later. Sleeping in became a mark of prestige. Meanwhile, those who lived near the gasworks — never located in a city’s high-rent district — endured foul-smelling and dangerous emissions.

(via)

It is pleasant to observe how free the present age is in laying taxes on the next. FUTURE AGES SHALL TALK OF THIS; THIS SHALL BE FAMOUS TO ALL POSTERITY. Whereas their time and thoughts will be taken up about present things, as ours are now.

See America First | The New York Review of Books

Speaking of bohemians, I like this bit from a 1970 review of Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant. (via I forget who)

The current generation of bohemians and radicals hasn’t decided whether to love or hate America. On a superficial level, the dominant theme has been hate—for the wealth and greed and racism and complacency, the destruction of the land, the bullshit rhetoric of democracy, and the average American’s rejection of aristocratic European standards of the good life in favor of a romance with mass-produced consumer goods. But love is there too, perhaps all the more influential for being largely unadmitted. There is the old left strain of love for the “real” America, the Woody Guthrie-Pete Seeger America of workers-farmers-hoboes, the open road, this-land-is-your-land. And there is the newer pop strain, the consciousness—initiated by Andy Warhol and his cohorts, popularized by the Beatles and their cohorts, evangelized by Tom Wolfe, and made respectable in the bohemian ghettos by Bob Dylan and Ken Kesey—that there is something magical and vital as well as crass about America’s commodity culture, that the romance with consumer goods makes perfect sense if the consumer goods are motorcycles and stereo sets and far-out clothes and Spider Man comics and dope. How can anyone claim to hate America, deep down, and be a rock fan? Rock is America—the black experience, the white experience, technology, commercialism, rebellion, populism, the Hell’s Angels, the horror of old age—as seen by its urban adolescents.

Then That’s What They Called Music! | The A.V. Club

“We begin a journey through pop’s recent past by examining the bestselling, major-label NOW That’s What I Call Music compilations.”