The greatest audience comment ever recorded is, I think, a remark overheard at a performance of Ernst Krenek’s Second Piano Concerto at the Boston Symphony in 1938. A Boston matriarch responded to Krenek’s twelve-tone discourse by saying, ‘Conditions in Europe must be dreadful.’

Tag: classical

Glenn Gould, March 1955, at the Columbia studio in New York during the recording sessions for the Goldberg Variations. Photo by Gordon Parks for LIFE. PIANIST GLENN GOULD | REJECTING THE ‘BLOODSPORT’ CULT OF SHOWMANSHIP « The Selvedge Yard.

When the Crescendo Is the Least of Your Worries by Christopher R. Graham – The Morning News

“After practicing with his iPod—and feeling pretty good, actually—novice Christopher R. Graham discovers the extreme fear of conducting a professional orchestra.” (via)

When the Crescendo Is the Least of Your Worries by Christopher R. Graham – The Morning News

Steve Reich’s “Clapping Music” performed by Lee Marvin and Angela Dickinson. (via) A scene from Point Blank, I believe. Here’s the score.

I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise…

This reminds me of what I called and still call one of my favorite pieces of music ever, Steve Reich’s City Life, which uses a bunch of samples from New York City street scenes: hawkers, sirens, car and boat horns, screeching tires, subway whooshings. Luckily all five parts are online for your listening pleasure.

La Mantovana – Wikipedia. A tweet from David Friedman (@ironicsans)…

La Mantovana – Wikipedia. A tweet from David Friedman (@ironicsans)…

‘Tree of Life’ trailer: http://bit.ly/i5RnkM Smetana’s ‘Moldau’: http://bit.ly/gSgHbP Israel’s national anthem: http://bit.ly/eXEDYS

…reminded me of this old, old, old song. I love that we’re still using 400-year-old melodies.

Poignance Measured in Digits – New York Times

July 16, 1989 article by Hans Fantel. He writes about a CD his father gave him, a Vienna Philharmonic performance of Mahler’s 9th–the very show that they’d attended together 50 years earlier, which also happened to be the last the Vienna Philharmonic would give before Hitler rolled in.

But it wasn’t the music alone that cast a spell over me as I listened to the new CD. Nor was it the memory of the time when the recording was made. It took me a while to discover what so moved me. Finally, I knew what it was: This disk held fast an event I had shared with my father: 71 minutes out of the 16 years we had together. Soon after, as an “enemy of Reich and Fuhrer,” my father also disappeared into Hitler’s abyss.

That’s what made me realize something about the nature of phonographs: they admit no ending. They imply perpetuity.

All this seems far from our usual concerns with the hardware of sound reproduction. But then again, speculating on endlessness may be getting at the purposive essence of all this electronic gadetry – its “telos,” as the Greeks would say. In the perennial rebirth of music through recordings, something of life itself steps over the normal limits of time.

(via Alex Ross’ new book)

Poignance Measured in Digits – New York Times

James Kibbie – Bach Organ Works

Internet treasure via Alex Ross: free downloads of all of Bach’s organ pieces. I’ve listened to about 2.5 of the 18 hours’ worth. So far so good. The only reason not to get these is if you don’t like Bach or organ or music, and you’d be wrong on all three counts.

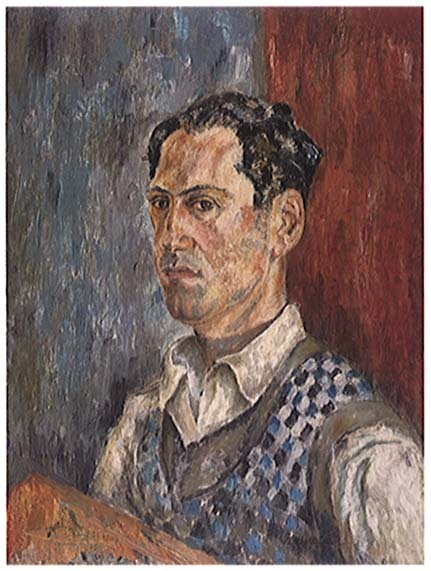

George Gershwin. Self-portrait.

Self-portrait by Darius Milhaud, owned by Dave and Iola Brubeck. Great story at The Rest Is Noise: Milhaud comes home. Brubeck named his oldest son Darius, by the way.

Classical Fans Tell Stories Of ‘First Loves’ : Deceptive Cadence : NPR

I was homeless, and working holding a sandwich board on the side of the road. It was so dull! I saved up for weeks and got a Sony Discman for $50.00. Now I had something to listen to while I worked. The Discman was so expensive that all I could afford was an Excelsior Gold recording of the fourth and sixth symphonies that was lying in a discount bin for a dollar-fifty. When I was playing it for the first time, in my board, pacing up and down the block — because if you stopped moving at anytime, the police would ticket you for loitering — I suddenly burst into tears. I felt like Beethoven was there with me, saying, “I know this sucks. But look— here is the whole world, outside, birds, the sky, the sun, and here you are! You are in it! Buck up!”

Classical Fans Tell Stories Of ‘First Loves’ : Deceptive Cadence : NPR

Peanuts, March 25, 1952 by Charles Schulz. Some pieces of music require a running start! Hell yes. From Schulz’s Beethoven: Schroeder’s Muse, an awesome 150+ page web exhibit from the Charles M. Schulz Museum and the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San José State University. Lots of strips and music samples and biographical details to peruse.

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould. Coming to Atlanta in November. What a character. I loved this one book about him, A Romance on Three Legs, and a buddy at work told me that Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould is also very good.

Leonard Bernstein’s score of former Philharmonic music director Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, which Alan Gilbert conducts next week at Avery Fisher Hall on September 29, 30, and October 1.

1-Bit Symphony. “1-Bit Symphony is not a recording in the traditional sense; it literally "performs” its music live when turned on.“ This is brilliant. (via)

Dr. Dre To Release Instrumental Hip-Hop Album About The Solar System | Gigwise

Oh hell yeah. (via). À la Holst:

It’s just my interpretation of what each planet sounds like… I’m gonna go off on that. Just all instrumental. I’ve been studying the planets and learning the personalities of each planet.

Dr. Dre To Release Instrumental Hip-Hop Album About The Solar System | Gigwise

Edgard Varèse does jazz. Cf. the score for Poème électronique. Also, there’s a Varèse blog and I didn’t know?!

[The Große Fuge is] an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever.

-Igor Stravinsky

Nice visualization, too.

A lovely little infographic from Neven Mrgan, comparing the durations of Gould two major recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations:

Here’s a little chart I made. Glenn Gould recorded two remarkably different versions of Bach’s ‘Goldberg Variations’. The 1955 version is fast, virtuosic, and energetic (even frenetic). The 1981 version is deliberately paced and elegant. They are both dizzying masterpieces.

Most people prefer one over the other. On an average day, I will favor the 1981, but only by about 5%. I am very glad that both of them exist.

A State of Wonder was one of my favorite albums of 2008. I’ve been meaning to go back and listen through again, but alternating between the 1955 and 1981 versions for each variation. I think I also prefer 1981 recording.