It seems like the big distinction between good art and so-so art lies somewhere in the art’s heart’s purpose, the agenda of the consciousness behind the text. It’s got something to do with love. With having the discipline to talk out of the part of yourself that can love instead of the part that just wants to be loved.

Tag: art

Scott Weaver creates a San Francisco toothpick city:

The lesson in this is, ‘What do we do with our time?’. And I love to create. I love to show people what can be done in life if you spend time to create. Use your imagination.

I like the idea that you let culture use you as its instrument. What gets in the way is being too clever, or worrying about how something is going to function, or where it’s going to be. When you start thinking of something as art, you’re fucked: you’re never going to advance.

Trash, Art, and the Movies

Your required reading of the week: Trash, Art, and the Movies. This piece from Pauline Kael appeared in Harper’s, February 1969. I found it in the American Movie Critics anthology and couldn’t put it down. It’s a fantastic essay about high art and low art, what makes movies fun and what makes them tedious. Some good bits…

On connecting with like-minded people (It’s more fun to meet someone who also likes Footloose than to meet someone who also likes, I don’t know, Lawrence of Arabia.):

The romance of movies is not just in those stories and those people on the screen but in the adolescent dream of meeting others who feel as you do about what you’ve seen. You do meet them, of course, and you know each other at once because you talk less about good movies than about what you love in bad movies.

On schooling and aesthetic development (being taught vs. learning to discern):

Perhaps the single most intense pleasure of moviegoing is this non-aesthetic one of escaping from the responsibilities of having the proper responses required of us in our official (school) culture. And yet this is probably the best and most common basis for developing an aesthetic sense because responsibility to pay attention and to appreciate is anti-art, it makes us too anxious for pleasure, too bored for response. Far from supervision and official culture, in the darkness at the movies where nothing is asked of us and we are left alone, the liberation from duty and constraint allows us to develop our own aesthetic responses. Unsupervised enjoyment is probably not the only kind there is but it may feel like the only kind. Irresponsibility is part of the pleasure of all art; it is the part the schools cannot recognize.

On “redeeming” pop trash with academic jargon (just enjoy it, folks!):

We shouldn’t convert what we enjoy it for into false terms derived from our study of the other arts. That’s being false to what we enjoy. If it was priggish for an older generation of reviewers to be ashamed of what they enjoyed and to feel they had to be contemptuous of popular entertainment, it’s even more priggish for a new movie generation to be so proud of what they enjoy that they use their education to try to place trash within the acceptable academic tradition.

[…]

We are now told in respectable museum publications that in 1932 a movie like Shanghai Express “was completely misunderstood as a mindless adventure” when indeed it was completely understood as a mindless adventure. And enjoyed as a mindless adventure. It’s a peculiar form of movie madness crossed with academicism, this lowbrowism masquerading as highbrowism, eating a candy bar and cleaning an “allegorical problem of human faith” out of your teeth.

Plaque with Medea’s Murder of Absyrtus by Martin Didier Pape. I think this will be my last selection from the Walters Art Museum. I love the odd body parts floating in the ocean. Such gore for the late 1500s.

I never think of anything as finished until it’s released. If you came round to my house one day and I said, “This is something I haven’t finished yet, but it’s going to be much better when I’ve mixed it,” and blah blah blah – all these defenses – and then I played it for you, that’s one thing. But if you pick up my album at a shop and take it home and put it on your record player and I’m not there to give you all those excuses, that’s quite a different thing. A work is finished for me when it’s no longer in the domain of my excuses about it.

Profile Head of a Young Woman by Leopold Carl Müller. The other half of the pair.

Profile Head of a Young Woman by Leopold Carl Müller. One of a pair, another selection from the Walters Museum that I really liked.

An Accident by Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret. “In this scene, a country doctor bandages a boy’s injured hand, while his family looks on with varying degrees of concern.”

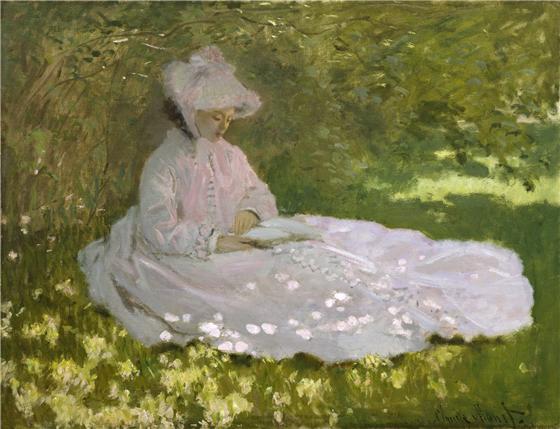

Springtime by Claude Monet. That dappled sunlight!

Paris Kiosk by Jean Béraud. If you find yourself in Baltimore like I did a few weeks ago, I suggest you visit the Walters Art Museum. Not only is it cheap, but they’ve got cool stuff AND they’ve got a spectacular online collection so you can re-visit the ones you loved. I’ll be sharing a few of mine over the next few days.

A View of the Bombardment of Ft. McHenry. I was in Baltimore a few weeks ago and stopped by Fort McHenry (Star-Spangled Banner, etc.). This painting was one of my favorites, if only for the trails on the bombs.

I love this post about measuring whether an artist is under- or over-valued. The method is pretty cool, basically comparing the Human Accomplishment ranking and the available Amazon music inventory, and making a rough P/E ratio. This post focuses on notable composers and it looks like Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque composers get shorted, while late Romantics (especially opera dudes) get more hype than they deserve. And you see the same sort of bias in the season programming of most major orchestras.

Anyway, two cool things this brings to mind. One, I like this idea of bubbles in culture. Reminds me of the vast difference in New York Times coverage of conflicts in Darfur vs. the Congo, though one area has been about 10 times as deadly. There are all kinds of interesting feedback loops that affect how we perceive and respond to our world. And two, realizing that there’s so much rough-and-ready data out there that we’ve unwittingly created, just waiting to be mined.

Warhol on good art vs bad art. Brilliant.

From an interview with Lynda Barry:

There isn’t much of a difference in the experience of painting a picture, writing a novel, making a comic strip, reading a poem or listening to a song. The containers are different, but the lively thing at the center is what I’m interested in.

[via austin kleon]

Brian Eno, Thinking about Miles Davis in an un-Miles Davis like way:

Miles was an intelligent man, by all accounts, and must have become increasingly aware of the power of his personal charisma, especially in the later years as he watched his reputation grow over his declining trumpeting skills. Perhaps he said to himself: These people are hearing a lot more context than music, so perhaps I accept that I am now primarily a context maker. My art is not just what comes out of the end of my trumpet or appears on a record, but a larger experience which is intimately connected to who I appear to be, to my life and charisma, to the Miles Davis story. In that scenario, the ‘music’, the sonic bit, could end up being quite a small part of the whole experience. Developing the context—the package, the delivery system, the buzz, the spin, the story—might itself become the art. Like perfume…

Professional critics in particular find such suggestions objectionable. They have invested heavily in the idea that music itself offers intrinsic, objective, self-contained criteria that allow you to make judgments of worthiness. In the pursuit of True Value and other things with capital letters, they reject as immoral the idea that an artist could be ‘manipulative’ in this way. It seems to them cynical: they want to believe, to be certain that this was The Truth, a pure expression of spirit wrought in sound. They want it to be ‘out there’, ‘real’, but now they’re getting the message that what it’s worth is sort of connected with how much they’re prepared to take part in the fabrication of a story about it. Awful! To discover that you’re actually a co-conspirator in the creation of value, caught in the act of make-believe.

Carp Leaping Up a Cascade by Katsushika Hokusai. I find this rather breathtaking.

The History of Visual Communication. Plenty of good stuff here. I like the care taken in the further readings & references at the bottom of each section.

A Day in the Life of a Musician by Erik Satie:

An artist must regulate his life.

Here is a time-table of my daily acts. I rise at 7.18; am inspired from 10.23 to 11.47. I lunch at 12.11 and leave the table at 12.14. A healthy ride on horse-back round my domain follows from 1.19 pm to 2.53 pm. Another bout of inspiration from 3.12 to 4.7 pm. From 5 to 6.47 pm various occupations (fencing, reflection, immobility, visits, contemplation, dexterity, natation, etc.)

Dinner is served at 7.16 and finished at 7.20 pm. From 8.9 to 9.59 pm symphonic readings (out loud). I go to bed regularly at 10.37 pm. Once a week (on Tuesdays) I awake with a start at 3.14 am.